Why we optimize the fun away: a case against the second screen

I’m going to make a case that the ease of access to information in video games can diminish the potential for fun. I’m not a Luddite and I’m not here to advocate for shutting down the Internet, but I do yearn for a time where looking up an answer wasn’t as easy, or at least wasn’t an immediate instinct.

Let me start at the beginning. In my childhood home, we didn’t have the Internet for a while, and I played games on our chunky beige PC completely offline. While certainly colored by nostalgia, having to figure out how to make my way through Hitman: Codename 47 levels, taking notes in my school notebook for Morrowind quests, or playing through Silent Hill or Resident Evil 2 completely blind were formative experiences. The world of the game was the only world that existed. There was no second screen, no wiki, no friendly voice on YouTube telling me where to go.

You see, I could spend hours, sometimes days, trying to figure out a solution to a puzzle or finding a unique way to work through a problem. And when that “Aha!” moment finally hit, it felt so incredibly satisfying. That success was mine and mine alone.

Today, I find myself easily frustrated when playing games, and I’m quick to look something up online, despite knowing it’s likely to ruin my fun. Why do I do it? Why do many of us do it? This isn’t just a matter of weak willpower. As Soren Johnson, lead designer of Civilization IV, famously said: “Given the opportunity, players will optimize the fun out of a game”. The nature of games and the culture around them has changed, often pushing us toward this path of least resistance. Let’s analyze how.

The games are broken

This one’s easy, and it’s the most corrosive problem. Because patching is easier than ever before, more and more games ship in a broken state. The problem is that this unreliability shatters a player’s trust. Is this an obscure quest feature, or is this a bug?

I was recently playing S.T.A.L.K.E.R. 2, and couldn’t find an artifact despite searching through every inch of a compound - and my detector was going crazy the whole time. Turns out the artifact fell through the floor, and I had to reload the game a couple of times and crouch in a very specific way to clip into the floor and grab it.

S.T.A.L.K.E.R. 2: Heart of Chernobyl: is this a feature or a bug?

S.T.A.L.K.E.R. 2: Heart of Chernobyl: is this a feature or a bug?

From that moment on, the trust is gone. Every time I’d run into any friction, my first instinct wouldn’t be to think harder; it would be to suspect the game is broken again. Sometimes it’d be a legitimate puzzle that I stopped myself from solving. But sometimes it’d be a bug, and I’m no longer willing to waste my time finding out. This isn’t a 2020s problem, either. Bethesda’s Oblivion was way ahead of its time in having game-breaking bugs in its main quest alone (hello, defense of Kvatch).

Look, I understand the pressure developers face - publisher deadlines, shareholder expectations, and the promise that “we can patch it later.” And we, as players, can share some blame too. We pre-order games, buy them on day one, and have collectively accepted that a day-one patch is just part of the experience now. But this cycle of broken releases teaches players that when something feels off, it probably is. We look up answers to every friction point because the industry has taught us that the friction might just be a flaw. And that’s a shame, because overcoming a well-designed challenge is the soul of gaming.

I know the hyper-optimized builds are there

One of the biggest challenges is that I know, for a fact, that hyper-optimized, mathematically “correct” builds are already out there. The moment I open a character creation screen, the ghosts of a thousand spreadsheets and build guides haunt my choices, removing the joy of discovery and customizability.

The latest example of this for me is Warhammer 40,000: Rogue Trader. Even though I loved the game’s world and would generally consider myself a tabletop nerd, the character creation, level-ups, and builds were just above my pay grade. The game asked me to invest a huge amount of time just to have a slightly viable build. I love deeply customizable systems, but the lack of a low skill floor harmed the experience. Yes, I could spend 30 minutes reading through every single talent for one character on one level-up, or I could open a browser tab and find a build that’s guaranteed to work.

Warhammer 40,000: Rogue Trader. Character screens have a steep learning curve, I’m sure somebody else can do better than me.

Warhammer 40,000: Rogue Trader. Character screens have a steep learning curve, I’m sure somebody else can do better than me.

Owlcat Games titles (like the aforementioned Rogue Trader and the Pathfinder games) are infamous for this level of complexity. But here’s the thing: compare them to something like Divinity: Original Sin 2 or even Baldur’s Gate 3. These games have equally deep systems, but they ease you in. Divinity: Original Sin 2 starts you with clear archetypes and slowly reveals the depth of its crafting and skill combinations. You can absolutely break the game with the right builds, but you can also bumble through with a weird necromancer-summoner-tank hybrid and still have a blast. The complexity is there if you want it, but it’s not mandatory from hour one.

This problem is a lot more prominent in online games. After all, it’s rude to suck at World of Warcraft. Bringing a non-meta build into a raid feels disrespectful to other players’ time. The social pressure to optimize removes any room for experimentation or personal expression.

The temptation is always there: play your way and risk being ineffective, or play the “right” way and guarantee progress? Too often, we choose the latter. But some games fight back. Elden Ring, for instance, has shown us that “suboptimal” often just means “more challenging,” and the community celebrates players who beat the game with nothing but a club or while wearing a pot on their head. These aren’t the mathematically best builds, but they demonstrate mastery and create better stories than any min-maxed character ever could.

The puzzles are obscure, not clever

Sometimes, the game itself is the problem. There’s a vast difference between a puzzle that is difficult and one that is simply obscure. A great puzzle respects your intelligence; it gives you all the pieces but trusts you to assemble them. Think of the intricate logic of Return of the Obra Dinn, where every clue you need is present somewhere on the ship. It’s hard, but it’s fair.

Return of the Obra Dinn: The solution is somewhere on this ship, I just have to keep looking.

Return of the Obra Dinn: The solution is somewhere on this ship, I just have to keep looking.

Portal and Portal 2 are masterclasses in puzzle design - each test chamber teaches you something new, and the solution always uses mechanics you’ve already learned. When you get stuck, you know the answer is there; you just need to think differently. Chants of Sennaar takes this even further, asking you to decode entire languages with nothing but context clues and pattern recognition. These games never make you guess what the designer was thinking; they make you think like the designer.

Compare that to how in Dark Souls, a game I deeply love and bring up in nearly every essay, to access the fantastic Artorias of the Abyss DLC, you must kill a hydra at the lake, reload the game, kill a golem in a cave at the back of the lake, then go to a completely different area and kill another golem to get an item, come back to the lake, possibly reload again, and finally enter the portal which leads to the DLC. It’s a sequence almost impossible to discover organically. It’s a sequence that sets a bad precedent.

You just need to ‘git gud’

Then there’s the culture. The mantra of “git gud” echoes around the most challenging games, particularly those from FromSoftware like Dark Souls or Elden Ring. And while there is immense satisfaction in mastering their combat, this philosophy often ignores that the games themselves can be incredibly opaque. Where do you find more sacred tears to upgrade your flask? How does poise actually work? Which obscure NPC questline do you need to follow to get that cool armor set? The community’s answer is often a shrug followed by, “just look it up.” Even in the pinnacle of challenging, satisfying game design, we are pushed toward guides to understand the very systems we’re supposed to be mastering.

Dark Souls: git gud.

Dark Souls: git gud.

And of course there’s the fear of missing out. Once we know a game has secrets, missable content, or hidden endings, the psychological pressure builds. We bought the game, after all. We want to extract every ounce of value from our purchase. More than that, we don’t want to be the person who missed the coolest moment, the best weapon, or the “true” ending. Gaming can become performative in a way - we need to prove we’re good at games, that we found all the secrets, that we didn’t miss anything. This completionist anxiety transforms exploration from a joy into a checklist. We’re no longer discovering; we’re collecting.

Simply put, I have less time

And ultimately, this all feeds into the simplest, most powerful reason: I just have less time today. As an adult with a job, a family, and a finite number of evenings to unwind, my gaming hours are precious. I’m not willing to invest a tremendous amount of time into a complex system, especially if it’s not showing early promise.

I think great games reward incremental progression and only later ask you to dive into their deepest systems. Fire Emblem: Three Houses nails this - you start by just moving units and attacking, then slowly learn about battalions, teaching, and relationship building. Each system is introduced when you’re ready for it, not dumped on you all at once. But when a game is potentially broken, and its systems are overwhelmingly complex from the start, my limited time makes the choice for me. I’m not going to spend my entire two-hour session stuck on one puzzle or respec-ing a character for the fifth time. The cost-benefit analysis of my own fun leads me straight to a guide. It’s a trade-off: I sacrifice the long-term satisfaction of discovery for the short-term guarantee of progress.

Fire Emblem: Three Houses avoids dumping all its systems onto the player, gradually revealing each gameplay element.

Fire Emblem: Three Houses avoids dumping all its systems onto the player, gradually revealing each gameplay element.

But all of this takes away from experimentation and discovery. Every time we tab out to a wiki, we rob ourselves of the very things that make games magical. We lose the chance to create our own weird, suboptimal-but-fun character build. We lose the thrill of stumbling upon a secret area by chance. We lose the quiet satisfaction of solving a puzzle after stepping away and thinking about it for a day. The journey of exploration is flattened into a series of tasks on a checklist, and our personal, unmapped adventure is replaced by a global, optimized route.

What we can do as players

So what can we do to reclaim this? While the issues are systemic, the change can start with us. First, we can recognize that the urge to look things up is often just anxiety in disguise - anxiety about wasting time, about being inefficient, about missing out. But here’s the thing: you can always replay a game. That missed quest or hidden ending? It’ll make your second playthrough feel fresh.

Try setting rules for yourself. Maybe you’ll only look something up after being stuck for a full gaming session. Maybe you’ll embrace your weird, inefficient character build and see where it takes you. Many games are specifically designed to let you succeed in multiple ways - lean into that freedom.

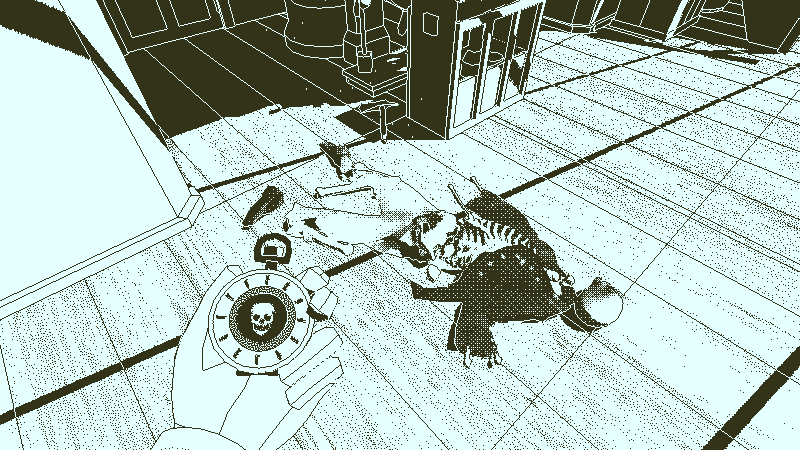

Inscryption: Most of the time you don’t even know what game you’re playing.

Inscryption: Most of the time you don’t even know what game you’re playing.

Seek out games that resist quick online lookups by design. Subnautica throws you into an alien ocean with no map and no waypoints, forcing you to navigate by landmarks and memory - there are guides, but they’re equally convoluted and require quite a bit of effort to follow. Inscryption constantly changes its own rules, making guides nearly useless. The Case of the Golden Idol presents mysteries that can only be solved by your own deduction (and looking up the solutions essentially bypasses the whole game). These games prove that discovery is still possible in the age of information.

Most importantly, we, as players, must remember that playing “wrong” is often more memorable than playing “right.” My most cherished gaming memories aren’t from following optimal paths - they’re from the time I got hopelessly lost in the Morrowind ashlands, the Dark Souls boss (or, let’s be honest, bosses) that took me fifty tries, or the Return of the Obra Dinn puzzle I finally cracked at 2 am. Those moments of personal triumph can’t be wikied; they have to be earned.

The hope remains

By choosing to engage with games on our own terms, we not only enrich our own experience but also send a message. Some developers are already recognizing this problem and designing their games to actively fight it. Games like Outer Wilds or Tunic are masterpieces of self-contained discovery. The Outer Wilds store page all but begs players not to spoil its secrets for others. The game knows that its magic is entirely contained within the player’s personal journey of understanding. It is a game that is about the process, not the destination. And the online communities reflect that culture.

Prey (2017) lets you tackle problems with whatever tools you’ve chosen to develop - hack the door, find a keycard, or turn into a coffee cup and slip through a crack. There’s no “correct” solution, just your solution. These games prove that it’s possible to create worlds so compelling that players instinctively know that looking up the answer would be robbing themselves of the true experience. When we celebrate and support these kinds of games, we signal to the industry that there is a market for experiences that trust the player.

That, right there, is the best way to play games. Not optimized, not efficient, not complete - but yours.

Comments

Respond directly on Bluesky (threads shown below) or Medium (view comments there).

Rooslawn's Unmapped Worlds

Rooslawn's Unmapped Worlds