When paying attention pays off

Morrowind’s “Atronach” birth sign, which you can select upon creating your character, doubles your amount of magicka (which you use to cast spells), but stops it from regenerating when you rest. You see, wizards can restore their magicka by resting - which really isn’t that hard to do. You don’t even need a bed - just plop yourself in the middle of a dungeon, recharge, and keep on fighting. The Atronach sign changes the flow. Now you’re dealing with a substantial pool of resources that doesn’t get restored for free.

This is Morrowind’s Tribunal Temple. Dunmer are… peculiar people. They leave the bones of their ancestors in the ash mounds inside temples, they believe it lets them commune with the dead.

This is Morrowind’s Tribunal Temple. Dunmer are… peculiar people. They leave the bones of their ancestors in the ash mounds inside temples, they believe it lets them commune with the dead.

At first, this feels like a tremendous handicap. Restore magicka potions exist, but they aren’t free. And while eventually money stops being a problem, early on you’re a bit strapped for cash. But then you visit a temple and pray by donating a humble sum at an altar - and would you look at that, your magicka gets restored. That’s neat, there are a lot of temples throughout the world - and you start noticing these all over. You stop by. Most older cities have a Tribunal temple in them, the original religion of the region. These temples always sport a half-dome shape and have a sizeable underground portion - they’re often in the most prominent part of the town - impossible to miss. The Imperials - who officially secured Morrowind as yet another Imperial province a few hundred years before the game starts - have built forts in strategic locations. There’s an Imperial Cult shrine in each fort, so you start being on the lookout for those as well.

This makes life much easier, as now you’re able to restore magicka in most settlements without relying on potions. And then you discover the trifecta of teleportation spells. The Mark and Recall spells, which let you place a mark in your current location and return to it later, the Almsivi Intervention which takes you to the nearest Tribunal temple, and the Divine Intervention which takes you to the nearest Imperial Cult. A plan begins forming: can I cast Mark where I stand, teleport to the nearest place of worship, and then Recall myself back? And just like that, the magicka crisis is solved. Feels great, and more importantly feels earned - you’ve overcome a pretty major disadvantage while reaping all the benefits the Atronach sign gives you.

But the story isn’t over. As you randomly cast either Divine or Almsivi Intervention spells, you notice that you get taken to different areas. You start noting patterns in shrine locations: indeed, the Empire only conquered certain parts of the island, while others eventually capitulated without further military action. So you start strategically using these spells to get yourself around. You know the fastest way to get back to civilization from a cave you just trekked a good hour to, and you execute it flawlessly. You feel mastery of the game’s travel systems - something I’ve written about before.

Contrast the Tribunal Temple with an Imperial Cult shrine. A utilitarian room in the castle. Just a priest, ceremonial kitchenware, and money - just how a religion is supposed to be.

Contrast the Tribunal Temple with an Imperial Cult shrine. A utilitarian room in the castle. Just a priest, ceremonial kitchenware, and money - just how a religion is supposed to be.

Something else happened too: you’ve essentially become a pilgrim who routinely visits and donates to places of worship. And you know a fair share about the game’s religions. The game never sat you down and explained the Tribunal, or the Imperial Cult, or why they occupy different parts of the island. You learned it because the mechanics made it useful.

I love when games do this - when gameplay pushes you to interact with the world, with lore, with systems that otherwise wouldn’t really have any mechanical effect. Just like that, for a savvy player, Morrowind turned religion into a system to engage with. And Morrowind isn’t the only game that does this.

Learning to read the ocean

Subnautica drops you into an alien ocean with a burning lifepod and basically nothing else. You have to explore, collect resources, and venture into increasingly dangerous parts of the ocean.

I still remember how disoriented I felt on my first playthrough. I have a decent sense of direction, but if not for the lifepod icon in my HUD, I would’ve never found my way back, no matter how many times I ventured out into the depths. I get out of the pod, start chasing after a fish, and immediately find myself lost - everything underwater looks the same. Or that’s what it feels like at first.

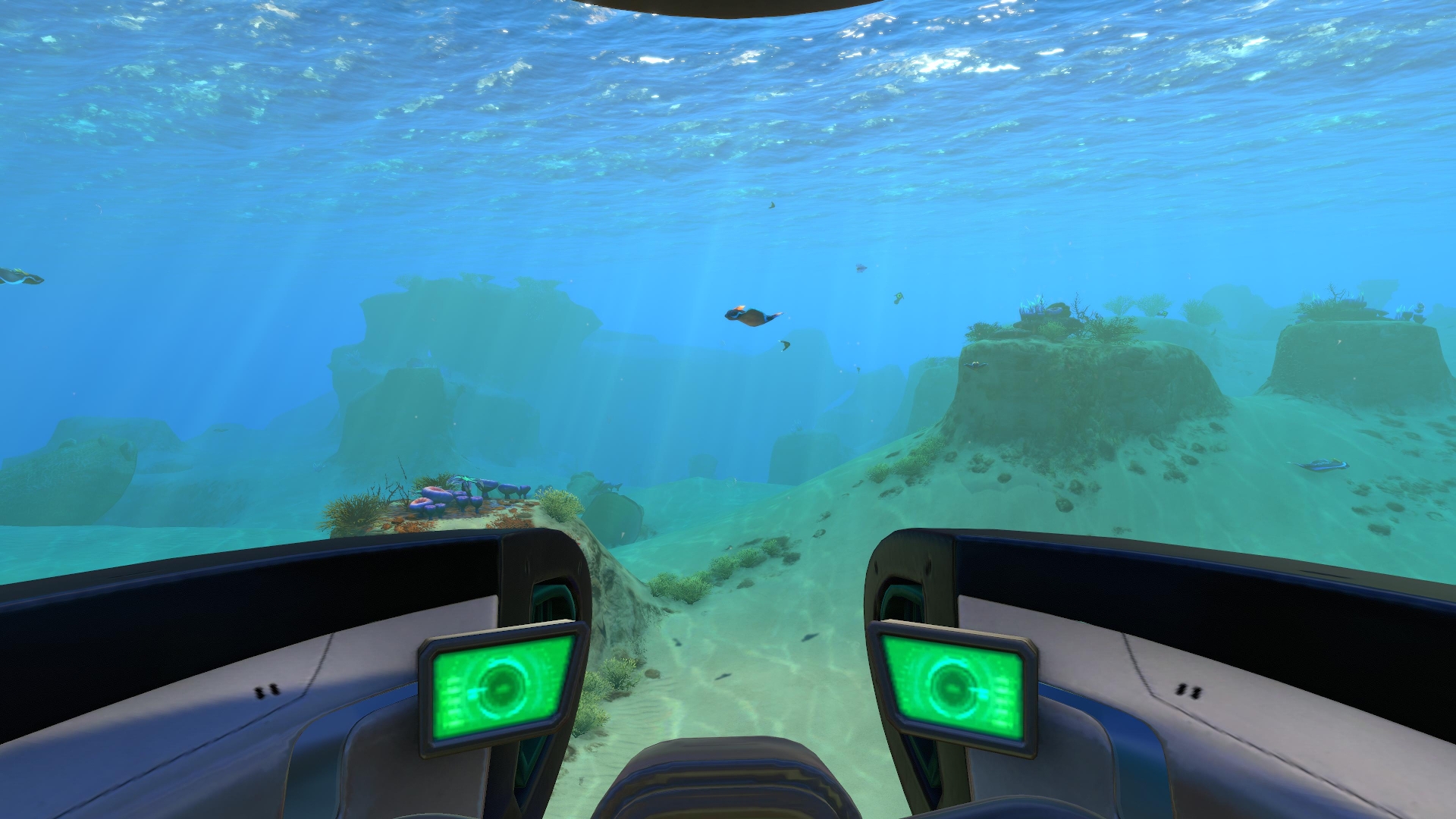

Subnautica’s shallows are safe and welcoming - with mostly docile sea life, and all the light filtering through. They feel vast and samey at first, but soon you realize that it’s a pretty compact area, and there are distinct landmarks dotted throughout.

Subnautica’s shallows are safe and welcoming - with mostly docile sea life, and all the light filtering through. They feel vast and samey at first, but soon you realize that it’s a pretty compact area, and there are distinct landmarks dotted throughout.

There are the shallows with a warm, sandy look, corals, and the little boomerang fish. There is the kelp forest, with its sprawling vines and aggressive stalkers. Or that plateau with the red-tinted grass, floaters, and the annoying little biting fish. Subnautica’s world is lovingly handcrafted, and it makes sense. There are hand-placed landmarks all over: a giant coral tube, an odd-looking cave entrance, a jagged canyon. You can even pop your head above the surface and find the towering wreck of the Aurora - the spaceship that got you stranded on the planet to begin with.

You can absolutely play Subnautica by staring at your compass and checking the wiki for coordinates. Plenty of people do, I’m sure. But if you pay attention to the world, you start navigating by landmark and instinct. You hear a Reaper Leviathan’s roar and you know to veer left because the one near the Aurora patrols a specific corridor. You spot the giant mushroom trees and know you’re in the right place for lithium. The jellyshroom caves have a specific entrance you remember because of that one time you barely escaped.

None of this is required. The game won’t quiz you. But the players who build that mental map - who learn the ocean as a place rather than a collection of coordinates - play a fundamentally different game. They navigate with confidence instead of anxiety (although the sense of dread Subnautica evokes never fully goes away, and I love the game for that). They route around danger instead of stumbling into it. The world stops being scary not because they got better gear, but because they understand it.

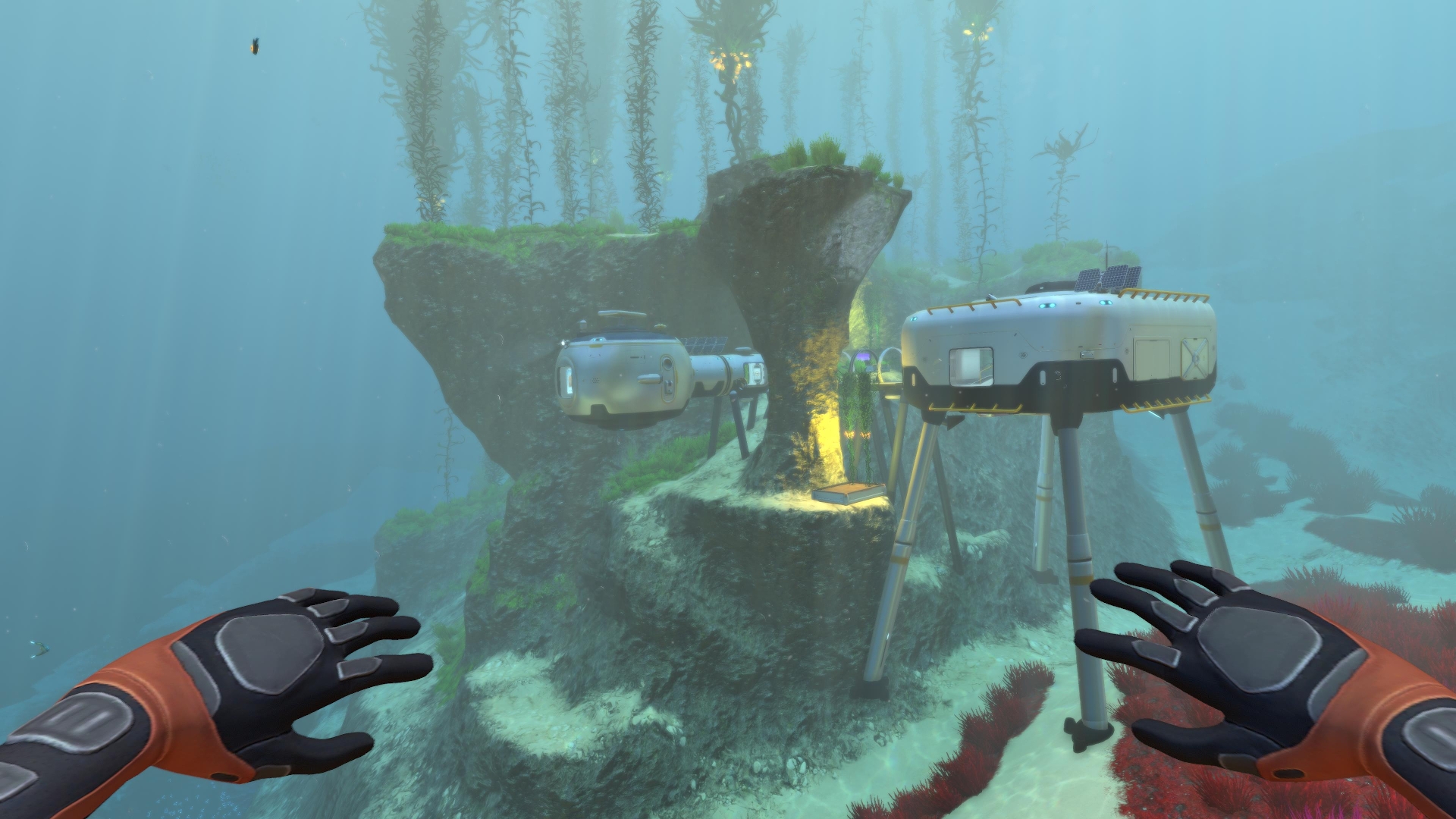

Here’s one of my bases in Subnautica. I find it to be perfectly located - it’s on the edge of three biomes, and has hidden entrances to a few more of the game’s areas nearby. I felt rewarded for picking this location.

Here’s one of my bases in Subnautica. I find it to be perfectly located - it’s on the edge of three biomes, and has hidden entrances to a few more of the game’s areas nearby. I felt rewarded for picking this location.

I think Subnautica works so well here because the world is genuinely distinctive enough to learn. Every biome looks, sounds, and feels different. You don’t learn the ocean because a codex tells you to. You learn it because you keep dying in the same spot and finally think: okay, what’s actually around me?

Reading the sky

Breath of the Wild does something similar, but with weather. Most open world games treat weather as decoration - it rains, things look pretty, maybe your character gets wet. In Breath of the Wild, weather will kill you. Lightning strikes if you’re wearing metal equipment. Rain makes climbing impossible. Cold and heat drain your health. You can brute force all of this with enough elixirs and armor sets. But the players who pay attention to the sky - who notice clouds gathering and unequip their metal gear before the first strike, who plan their routes around the rain, who spot updrafts near fires and use them to glide - those players move through Hyrule with a kind of grace that inventory management can’t replicate.

Breath of the Wild teaches you to pay attention to your surroundings. Some systems are taught more explicitly - like the heat and cold. Some - like lightning strikes - the players pick up on their own.

Breath of the Wild teaches you to pay attention to your surroundings. Some systems are taught more explicitly - like the heat and cold. Some - like lightning strikes - the players pick up on their own.

And it goes beyond weather. Fire spreads upward. Metal conducts electricity. Round things roll downhill. None of this is explained in a tutorial - you discover it by experimenting, by being curious. And once you understand these rules, the world opens up. There’s a moment - and I think most Breath of the Wild players have had it - where you stop opening the map to figure out where to go, and start looking at the actual landscape instead. That mountain looks interesting. There’s smoke over that ridge. Is that a shrine on that island? The game rewards you for looking, consistently. Not with a popup or an achievement - but with things to find that make you feel like you’re actually exploring rather than following a checklist.

Other worlds worth reading

This shows up in different flavors across games, and the reward isn’t always mechanical.

Outer Wilds is probably the purest version of this - a game where paying attention is literally the only progression system. Your character never levels up, never gets new gear. The only thing that changes is your understanding of the solar system. I’ve written about this at length, so I won’t belabor the point - but Outer Wilds takes what other games treat as an optional reward and makes it the entire game.

Outer Wilds excels at recontextualizing locations as you learn more about them.

Outer Wilds excels at recontextualizing locations as you learn more about them.

Tunic does something adjacent. It looks like a cute isometric Zelda-like - and it is - but scattered throughout the world are pages of an in-game manual written in a language you can’t read. You can finish the game without engaging with them. But players who actually study the pages - cross-referencing diagrams with the world, taking the gibberish seriously - discover hidden mechanics, secret systems, and a whole other game underneath the cute one. Paying attention to Tunic doesn’t just make it easier. It reveals there was more game than you realized.

Elden Ring and the broader Souls series reward attentive players differently - with narrative. You can finish these games without engaging with a single NPC questline. Most players probably do, given how obscure and easy to break these quests are. But the players who talk to everyone, who return to check on characters, who follow cryptic hints across the world - they get to see some genuinely great character arcs play out. Ranni’s questline, Blaidd’s fate, Alexander the jar warrior’s journey - none of these make you mechanically stronger in any meaningful way. But they make the world feel inhabited, and the reward is watching these stories through.

Oh, oh, and then there are the item descriptions. If you haven’t played any of the Soulslike games - the lore is mostly told through item descriptions. You’d find an armor set, and each piece will provide a bite sized piece of information about the world - how Artorias the Abysswalker, well, walked the abyss, or liked his dog very much. I promise you it makes sense and matters.

Dark Souls feeds you lore tidbits through occasional cryptic dialogues, but mostly through short item descriptions like this one. You get the satisfaction of piecing the narrative together.

Dark Souls feeds you lore tidbits through occasional cryptic dialogues, but mostly through short item descriptions like this one. You get the satisfaction of piecing the narrative together.

I recently stumbled on something similar in Tainted Grail: Fall of Avalon - a smaller, less well-known game (spoiler in this paragraph). I was snooping through a side quest I didn’t have to do, talking to people I didn’t need to talk to, and I learned something genuinely significant about the world’s lore - that Merlin didn’t create the Menhirs, the mysterious structures that are central to the game’s premise. I was just curious, and the game rewarded that curiosity with a piece of understanding that recontextualized a big part of the story early on. That felt great.

So what?

These games put things in the world and trust you to find them. They don’t highlight the important stuff in yellow. They don’t gate it behind a codex entry you’ll never open (be honest, you don’t read those - no matter how much you promise yourself you will). They put it in the geography, in the weather, in the scattered pages of a manual, in a side quest you didn’t have to take - and they wait.

I didn’t learn about the Tribunal because a loading screen told me. I learned about it because I needed magicka and the temples had it. I didn’t memorize Subnautica’s ocean because I studied a wiki. I memorized it because a Reaper Leviathan chased me through the crash zone and I never forgot which way was safe.

I keep thinking about why this matters to me specifically, and I’m not sure I have a clean answer. I play many games, and I often think about ways I enjoy them, and I often purposely try to force myself to be immersed into the game’s world, lore, characters - everything. And it’s really nice when games pull me in, when I remove that meta-level of thinking, when I get curious and excited - and the game rewards me for understanding the world.

Or maybe it’s simpler than that. Maybe I just like it when a game treats its world as something worth knowing, and trusts me to agree.

Comments

Respond directly on Bluesky (threads shown below) or Medium (view comments there).

Rooslawn's Unmapped Worlds

Rooslawn's Unmapped Worlds