What makes a procedural world have a soul?

Procedural generation promises endless replayability… but does it deliver? Rarely. Procedurally generated worlds often feel hollow, empty, and soulless - a void where an expression of a creator could’ve been. I hate procedural generation in video games.

Except for when I love it. And that love almost always stems from games where the generated content feels like it has a soul. Let me explain.

Note: All the games in my examples are great games, made by passionate teams with clear love and care. I enjoy many of these titles, and the ones I don’t - I recognize to be quality games. This is an opinion piece on procedural mechanics, not an attack on games.

Look - I love the atmosphere of Valheim: the warm hearth, the dark night, monsters besieging the dwelling you worked so hard to build, and the soundtrack just feels like a warm wool blanket around your ears. It’s a cozy survival game, made even cozier by the hostile wilderness.

Even the Valheim merchants (finding whom is a dreadful process) look nice and cozy.

Even the Valheim merchants (finding whom is a dreadful process) look nice and cozy.

But I hate exploration in Valheim. Meadows look welcoming, until you realize that they stretch for miles, with repetitive landscapes, same-looking shacks, and unending coastlines. You’re forced to use a map to make any sense of the world - and there’s no reason to pay attention to your landscape or landmarks. If you want to find the rare merchants (essentially required for progression) - you must use a map, because the land is vast, and the merchants are unassuming. Entering the Black Forest for the first time was awe-inspiring and scary, until I realized it’s just procedurally generated blackness for miles.

Just like the blackness of space in No Man’s Sky as you fly through yet another star system. Yes, this planet is a slightly different shade of red, and the creatures on the planet might have slightly bigger heads or maybe an extra arm or two - but it’s the same system you’ve seen hundred times over. There are ruins on the surface, a space station in the middle, and oddly cobbled together spaceships flying everywhere. And I know many players look at the vast universe of No Man’s Sky and see opportunity, wonder, and beauty - and that’s great (good work, Hello Games) - but I see repetition.

Elite Dangerous is guilty of this too - although I’m more likely to forgive tedious exploration and repetitive worlds given how great it feels to fly your ship (have you tried Elite Dangerous with VR and a HOTAS? It’s a life changing experience).

Remnant: From the Ashes lost me after I walked through exactly the same city block for the third time. Astroneer caves are vast, but there’s nothing interesting and truly unique within, other than being something to get through on your way to the planet core. Planet surfaces aren’t better. Just like the planets in Empyrion: Galactic Survival - vast, boring, unimaginative.

It’s not just the exploration - radiant quests of Fallout 4 makes me want to pull my hair out. A writer hasn’t bothered to write up this quest line, and I’m expected to dedicate my time playing through it? No, just no.

Fallout 4’s Preston Garvey is quick to remind you that another settlement needs your help.

Fallout 4’s Preston Garvey is quick to remind you that another settlement needs your help.

Our brains are very good at recognizing patterns, and you start seeing patterns with procedural generation very quickly. It’s hard to unsee these patterns, and it’s just a constant reminder that you’re playing a game, engaging with the content the creator didn’t bother to make.

This is why we’ve gotten tired of the Ubisoft formula (I couldn’t resist a jab at a large corporation): after you’ve played some, you know exactly what to expect, and the game will fail to surprise you.

But then, then there are great games that employ procedural generation to their benefit, and do so well. Minecraft, Terraria, and even less known Starbound - meaningfully incorporate procedural generation as part of a greater whole. You discover a new biome - and now there’s yet another set of materials for you to play with, or a new set of enemies to defeat.

Avorion gets away with procedural generation through the sheer inventiveness of its compelling ship building mechanics - it’s so fun to build ships, that it doesn’t matter where you’re flying them - your fleet is the game.

And there are games that make procedural generation a critical part of their gameplay - Dwarf Fortress being the king under the mountain here, with the whole history of the world - with wars, strives, and lost civilizations, being generated before you even set foot into the world. But the generation here is oh-so-complex and well made, and critically it sets the stage for you and your dwarfs to make meaningful and memorable stories. More accessible Rimworld does the same, on a much smaller scale.

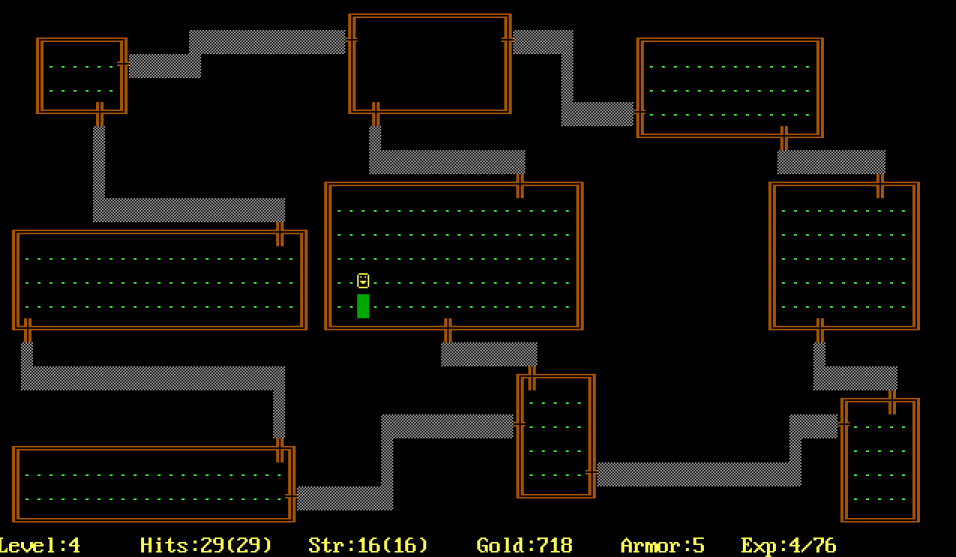

This is what peak adventuring looked like in 1980’s Rogue.

This is what peak adventuring looked like in 1980’s Rogue.

Roguelikes can do well with procedural generation too. The original 1980 Rogue worked because your imagination was left to fill in the blanks, and the due to permadeath, every new room feels tense - not knowing what’s ahead is core part of gameplay. Roguelikes wouldn’t be as fun if you knew what’s behind that door on the second run. Even more modern spins, like more classically inspired Barony, a space shooter Void Bastards, or mayhem covered Streets of Rogue benefit from relatively small, finite, contained procedurally generated spaces.

The procedural generation in these cases is just here to provide randomized arenas for a strong and engaging core gameplay loop (hey, Rogue gameplay was ahead of it’s time in the year 1980).

So, what makes procedural generation truly great? It hinges not simply on its existence, but on its purposeful integration and ability to convey that elusive soul. This soul isn’t mystical, it’s the tangible outcome of deliberate design. It manifests primarily when the procedural elements either:

- Deeply connect with and elevate the game’s core systems: The randomness isn’t arbitrary; it provides varied inputs for robust, interacting systems, leading to emergent outcomes that feel surprising yet internally consistent.

- Gracefully recede into the background: It provides fresh backdrops and novel layouts without impeding meaningful player experience or becoming the primary, often repetitive, feature.

Many games use procedural generation as a substitute for deliberate design, prioritizing vastness for vastness’ sake. These worlds are massive, but their content often feels bland, repetitive, and devoid of character. Pattern recognition kicks in, and when procedural generation lacks this integrated soul, we quickly see the seams. That transparency breeds a sense of emptiness and a constant reminder that we’re engaging with content the creator didn’t quite bother to make.

But when done right - with intent, with curation, and with a true connection to the gameplay - procedural generation can create experiences that are genuinely endless, not just endlessly boring. It doesn’t just fill space; it builds worlds that feel alive.

Comments

Respond directly on Bluesky (threads shown below) or Medium (view comments there).

Rooslawn's Unmapped Worlds

Rooslawn's Unmapped Worlds