Ugh, I'm too good at reading games

Give me ten minutes with an RPG and I’ll tell you which stats are dump stats. Drop me in a survival game and I’ll identify the tech tree’s critical path before I’ve built my first workbench. I see the skinner boxes, the content padding, the level-gated areas pretending to be mysterious.

I’ve written about this before - how I learned the language of games, moved from wonder to craft, from feeling to analysis. And most of the time, I’m fine with that trade. Understanding why something works doesn’t ruin it, because I have newfound appreciation for the games. Mostly.

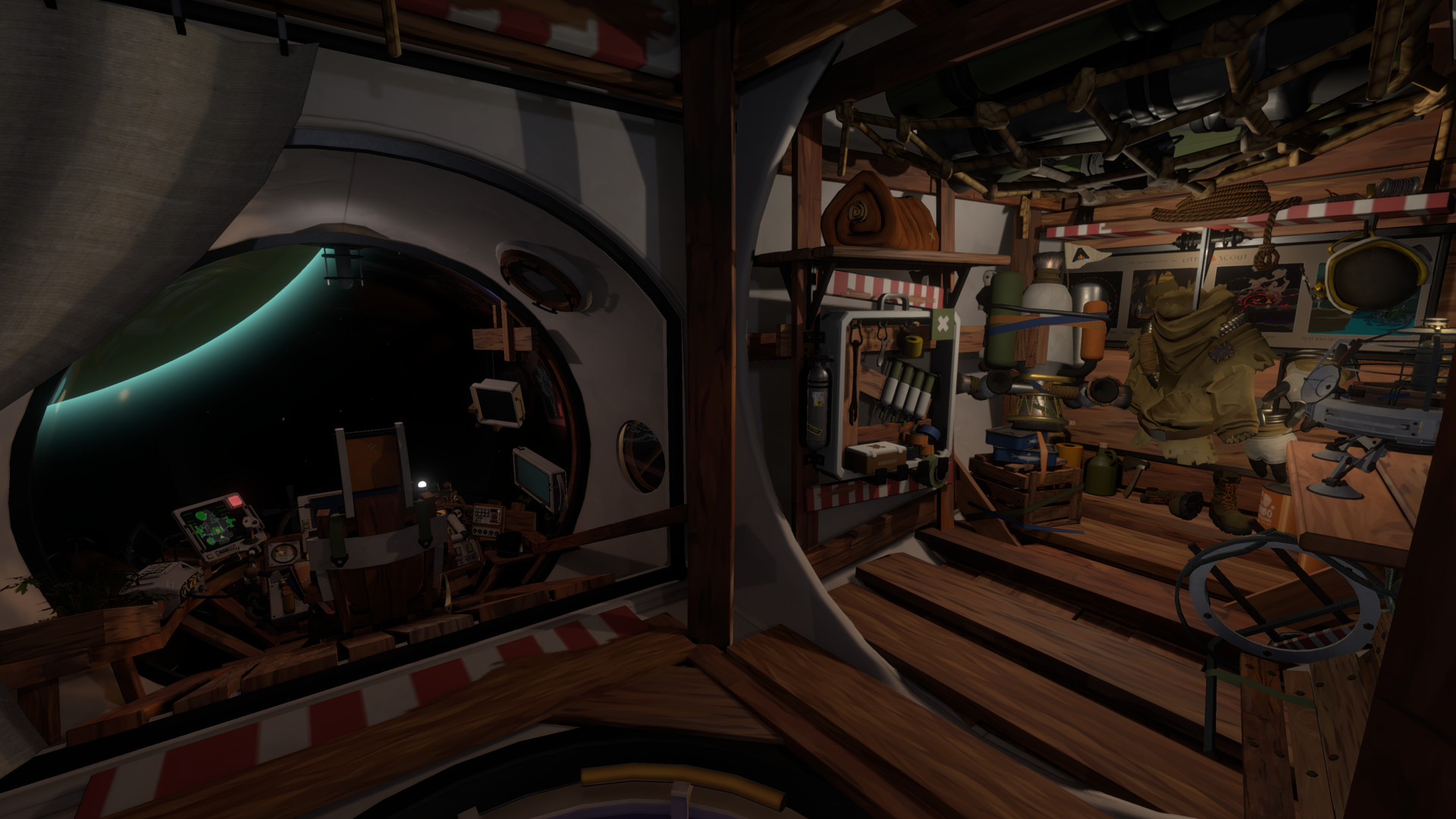

Outer Wilds: This is your cozy little spaceship, your unchanging companion - with no upgrades or skill trees.

Outer Wilds: This is your cozy little spaceship, your unchanging companion - with no upgrades or skill trees.

But sometimes I miss being lost.

Not frustrated-lost. Not clunky-game-design-lost. That childlike confusion where you don’t even know what you don’t know. Where the next step forward isn’t on a wiki, because you haven’t figured out what question to ask yet. Or better, you don’t think about wikis, because you’re so engrossed by the game.

And here’s the thing: some games manufacture that feeling on purpose, and do so oh-so-well. They strip away the numbers, the unlocks, the skill trees - and leave you with nothing to level up except yourself. Let me share my love for those games with you.

Your character doesn’t grow, but you do

Outer Wilds is one of my favorite games of all time, and I will keep talking about it until everyone I know has played it (if you haven’t - go play it now, or I’m going to spoil the fun for you).

Here’s the premise: you’re an astronaut in a tiny solar system, and you have 22 minutes before the sun explodes. Then you loop back to the start. Your ship is the same. Your tools are the same. Your character has the exact same capabilities in minute one as they do in hour twenty.

You know what changes though? You.

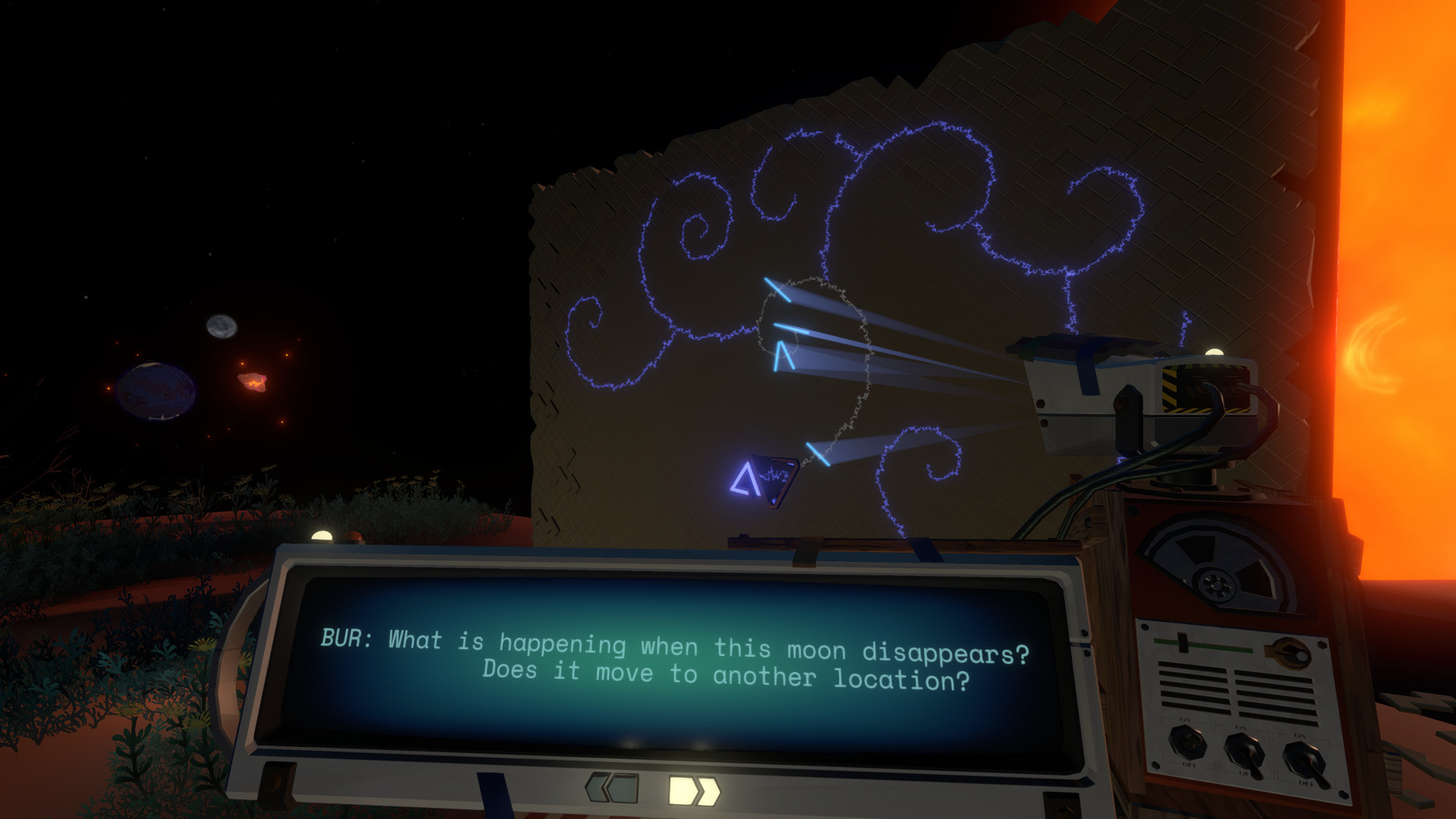

Every clue you find, every writing etched on the wall you decipher in Outer Wilds is a piece of the broader puzzle. Better, these pieces indirectly hint at the things you can do in the world.

Every clue you find, every writing etched on the wall you decipher in Outer Wilds is a piece of the broader puzzle. Better, these pieces indirectly hint at the things you can do in the world.

You noticed something weird on that one planet. You translated a piece of text that gave you a hint. You figured out how to reach a place that seemed impossible. The game’s progression system is entirely, completely, 100% located inside your skull. There are no unlocks. There are no upgrades. There’s only understanding.

Figuring something out feels so much more satisfying than getting a rare loot drop in an RPG. In fact, I’m having a hard time coming up with a single specific example as I write - it’s in the back of my mind, but case and point - loot ain’t as memorable. But I remember exact moments when things clicked, like figuring out how quantum objects work in Outer Wilds, and further, how to exploit the way they work to my advantage. I won’t spoil the game any further - if you know - you know. It hits different.

And once you understand - once you really understand what’s happening and what you need to do - you could start a fresh save and finish the game in about twenty minutes. Like a speedrunner. The game hasn’t changed. The knowledge has.

This is knowledge-based progression in its purest form. And it’s intoxicating.

The foreign language, on purpose

I think there’s a reason this style of game resonates so deeply with me specifically.

When I was a kid, playing games in English, which I couldn’t understand, everything was mysterious by default. I didn’t know where to go in Resident Evil 2 because I couldn’t read the hints. I didn’t understand Deus Ex’s plot because the dialogue was gibberish to me. The mystery wasn’t designed - it was a byproduct of my own ignorance.

Games like Outer Wilds and its excellent DLC Echoes of the Eye deliberately recreate that feeling. They want you confused. They want you piecing together fragments. They’re handing you a puzzle box with no instructions and trusting you to figure things out.

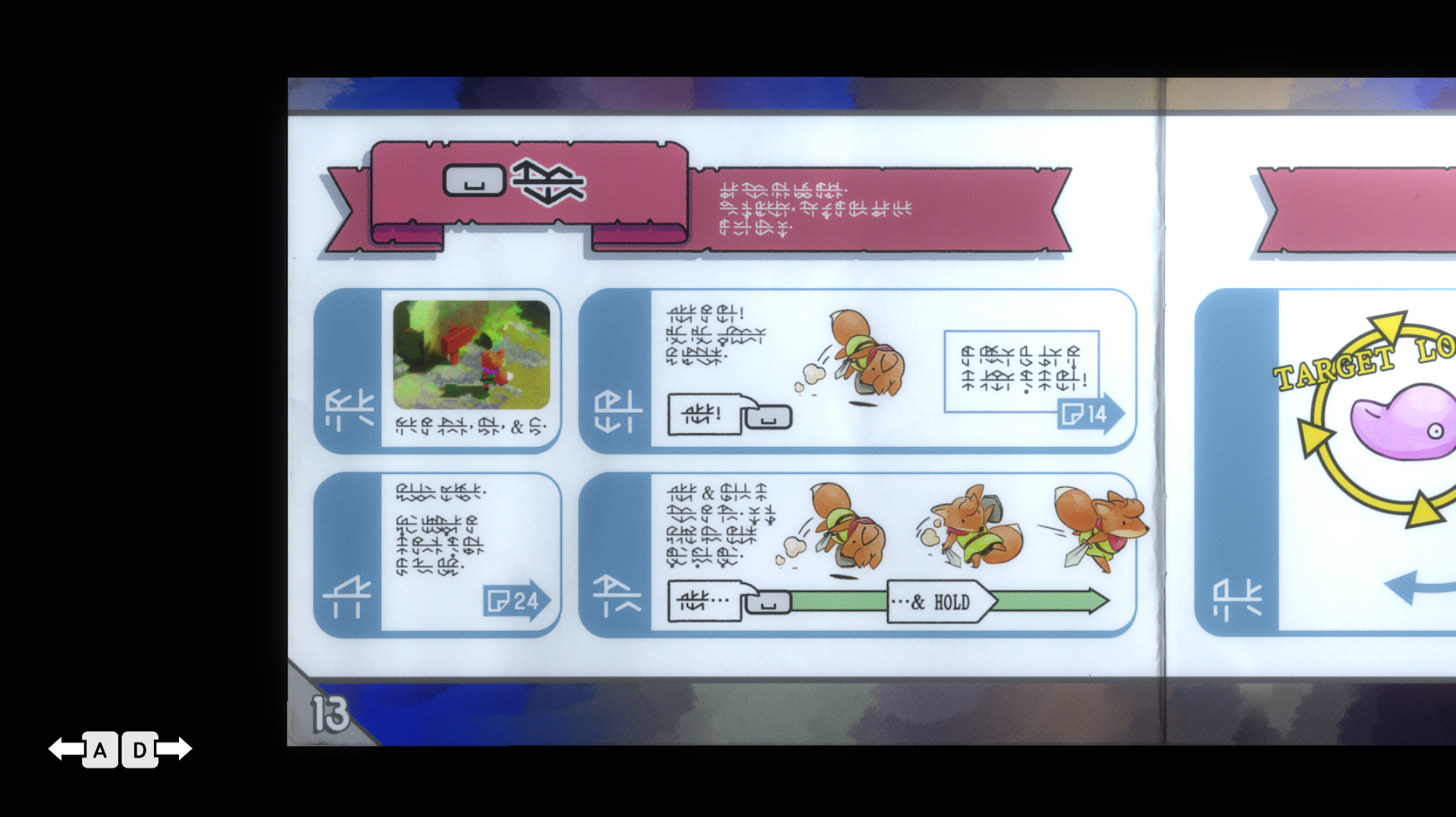

Tunic features an in-game manual in a gibberish language, complete with notes on the margins and puzzle hints left by the game’s previous owner.

Tunic features an in-game manual in a gibberish language, complete with notes on the margins and puzzle hints left by the game’s previous owner.

Tunic is another excellent example of this game design principle - it’s a game about playing a game with a manual written in a language you can’t read. You find pages scattered throughout the world, and slowly, painstakingly, you piece together how the game actually works. Things that seemed like decoration become meaningful. Mechanics you ignored become essential.

Tunic hits even harder after spending so much time with a retro handheld this year. I forgot how much older games (up to and including some PlayStation 1 era titles) relied on you using the manual. There are no in-game tutorials or button pop-ups, and even the game’s story is often relegated to an intro in a booklet. You’re expected to read the manual before playing the game - playing a game without a complete manual is like deciphering a puzzle.

Which is what Tunic did. Clever.

The deduction games

Not all knowledge progression is quite so freeform. There’s a whole genre of games that structure the “figuring things out” into something more puzzle-like.

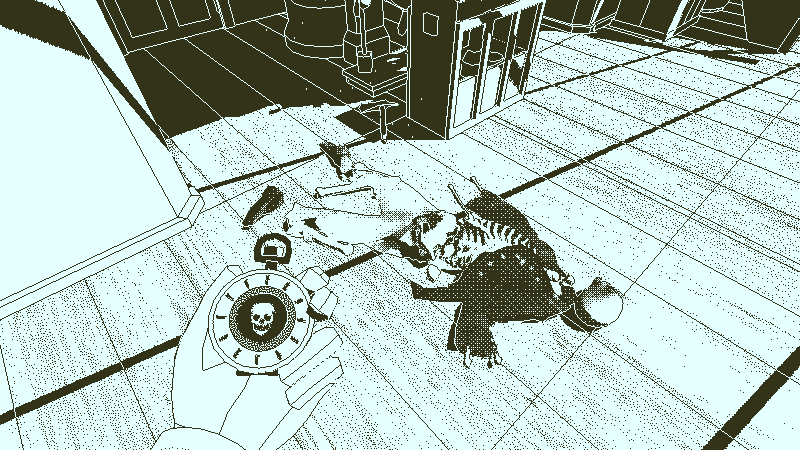

Return of the Obra Dinn hands you a ship full of corpses and asks: what happened to each of these sixty people? You have a magic pocket watch that lets you see their moment of death. That’s it. No quest markers. No highlighted clues. Just observation, deduction, and a spreadsheet of fates to fill in.

Return of the Obra Dinn: It is just your magical timepiece, a ledger, and your wit. There are 60 fates to determine.

Return of the Obra Dinn: It is just your magical timepiece, a ledger, and your wit. There are 60 fates to determine.

Beyond that, you figure out the rules of the game - the approaches for solving the mystery - on your own. I like when games respect your intelligence. It’s not a hard game by any means, and it employs many clever tricks to make the game easier (like confirming every three correct guesses you make) - but it expects you to put the work into figuring things out.

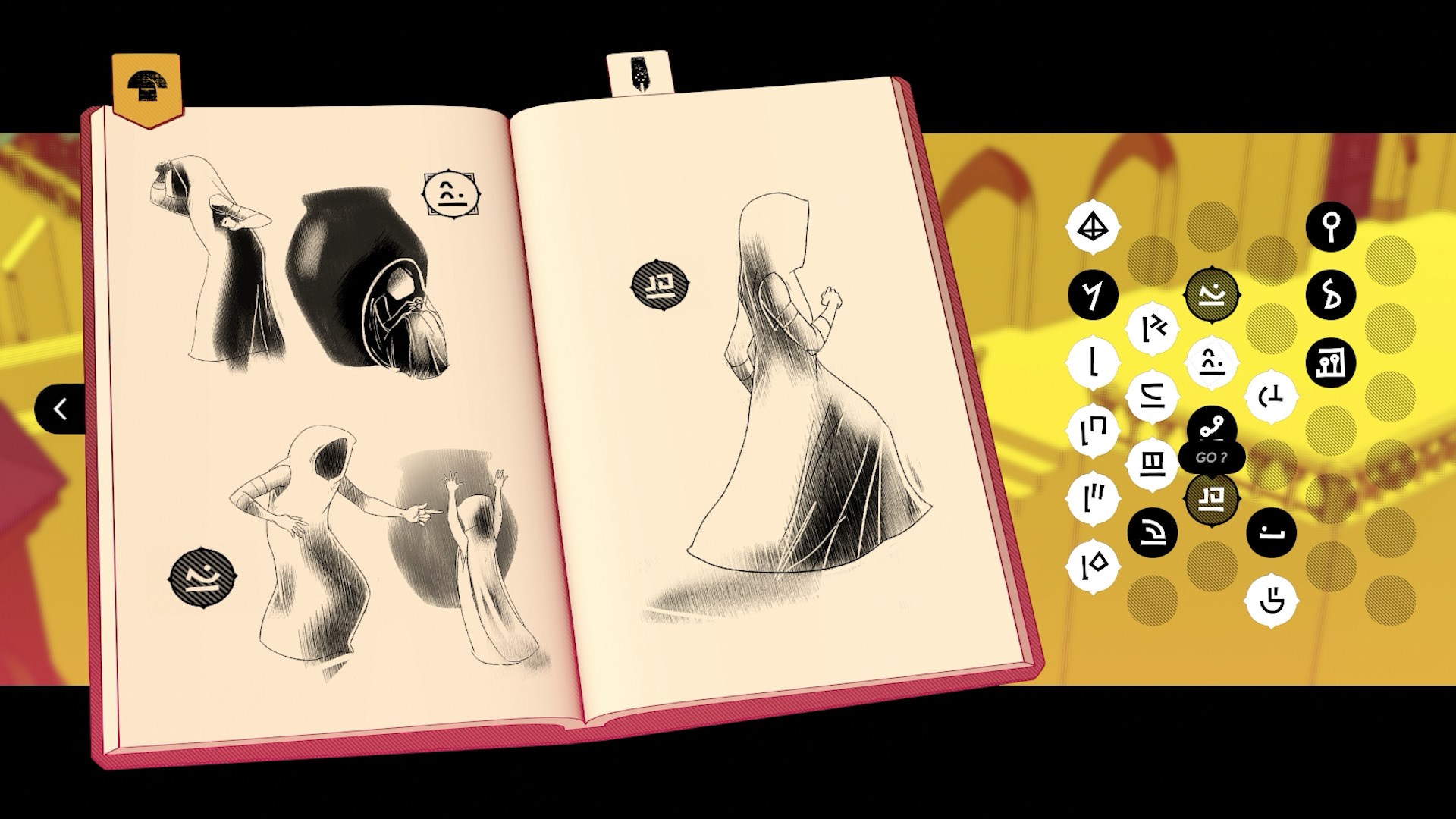

The Case of the Golden Idol does something similar - frozen panoramas of death, and you need to piece together names, motives, and methods from visual clues and scattered documents. Chants of Sennaar drops you into a tower where each level speaks a different language, and you speak neither of them, and you need to decipher them through context and observation.

Just like in Return of the Obra Dinn, Chants of Sennaar lets you know when you solve a number of the game’s puzzles correctly.

Just like in Return of the Obra Dinn, Chants of Sennaar lets you know when you solve a number of the game’s puzzles correctly.

These games share DNA with Outer Wilds - your character doesn’t level up, you do - but they provide more structure. There’s a right answer. There’s a solution. The joy is in the deduction, in feeling clever, in that moment where disparate clues suddenly snap together.

I think this is why puzzle games in general appeal to me more as I get older. Traditional progression - bigger numbers, shinier loot - starts to feel hollow when you’ve seen the pattern a thousand times. But a good puzzle? That’s new every time. You can’t grind your way to a solution.

The meta-knowledge layer

Here’s where it gets weird: knowledge-based progression exists in many games, even when it’s not a central game mechanic. We’re in the obligatory Elder Scrolls section of the essay.

There’s a YouTuber who does Morrowind challenge runs - Just Background Noise, and every single run starts the exact same way: an optimized route to pick up the game’s strongest items - scholar’s ring, bittercup, yada-yada. Within twenty minutes, this naked level-one prisoner is wielding god-tier equipment and is ready to kick Dagoth Ur’s butt.

If you’re a seasoned Morrowind player, you may notice the enchanting skill of 631. That’s 631 out of 100. There’s a whole different level to this game once you figure out how it works.

If you’re a seasoned Morrowind player, you may notice the enchanting skill of 631. That’s 631 out of 100. There’s a whole different level to this game once you figure out how it works.

The game didn’t design this as a progression mechanic. But for players who know, it absolutely is. The knowledge of where things are - what’s valuable, what’s breakable, what’s exploitable - becomes its own power curve. Your first Morrowind playthrough and your tenth are fundamentally different games, not because of any save file, but because of what’s in your head.

Another one of my personal favorites - Subnautica - does this too, in a softer way. Sure, there’s a tech tree and upgrades. But so much of the game is really about knowing. Knowing where the blueprint fragments are. Knowing which biomes are safe and where to find upgrade materials. Knowing where the resources are, where the story beats are, where the leviathans patrol.

On a replay, Subnautica becomes cozy - you know exactly where to go, exactly what to build, exactly how to avoid the scary parts. The game hasn’t changed. You have. Subnautica isn’t special in this way, you could say most games become cozy once you truly understand how they work and where everything is.

Why this matters (to me, anyway)

Here’s my theory about why knowledge-based progression hits different.

Traditional progression respects your time. Put in the hours, get the rewards. It’s transactional, predictable, almost contractual. And that’s fine - I’ve sunk hundreds of hours into games with XP bars and I’ll sink hundreds more. Hello, Old School RuneScape.

But knowledge-based progression respects your intelligence. It trusts you to figure things out. It doesn’t gate content behind grinding - it gates content behind understanding. And when you finally break through, when the pieces click into place, the satisfaction isn’t “I earned this through persistence.” It’s “I earned this through thinking.”

And I want to make a distinction - it’s not about players being smart. It’s about the games designed to make you feel smart. You aren’t automatically smarter because you rolled credits on the Talos Principle over a Call of Duty campaign.

That feeling of being smart? Rare in games. I mean puzzles in AAA games are laughable - you’re telling me a millennia of adventurers couldn’t match three symbols on these rotating pillars? Those puzzles are there to break up combat, not to challenge you.

Games built around knowledge progression don’t condescend. They trust you with genuine confusion, and genuine solutions, and the genuine satisfaction of bridging the gap yourself.

The unreplayable masterpiece

There’s a tragedy to pure knowledge-based games: you can only play them once. I don’t ever want to get head trauma, but if I do, I hope I’ll forget everything I know about Outer Wilds only to rediscover the game again.

I can replay Morrowind forever - there are different builds, different factions, different ways to break the game. I can replay roguelikes - the randomization keeps things fresh. But Outer Wilds? Once I know, I know. The mystery is solved. The magic is spent.

I finished Outer Wilds years ago, and I still think about it, and I haven’t touched it since, and I probably never will. Not because I want to replay it - I can’t, not really - but because it sits in this weird category of “experience I had” rather than “game I played.”

That’s Old School RuneScape. You can sink hundreds of hours, thousands of hours into this game. I wish I could do the same with Outer Wilds, but alas…

That’s Old School RuneScape. You can sink hundreds of hours, thousands of hours into this game. I wish I could do the same with Outer Wilds, but alas…

And maybe that’s the through line here. When I was a kid fumbling through Resident Evil 2 in a language I didn’t speak, those weren’t really games I played either. They were experiences I had. Mysterious, confusing, impossible to fully understand - and impossible to ever have again in the same way.

I learned English (barely). I learned to code (passably). I learned how games work, how they’re built, what tricks they use. I got fluent in all of it. And somewhere along the way, most games stopped being experiences and started being… games, just more content to consume.

But every now and then, something like Outer Wilds comes along and makes me feel like that confused kid again. Not because I can’t understand - but because the game is actively, lovingly, brilliantly withholding understanding until I earn it.

_If you enjoyed this essay, consider an adjacent piece on abundance, choice paralysis, and bootleg CD pirates.

Comments

Respond directly on Bluesky (threads shown below) or Medium (view comments there).

Rooslawn's Unmapped Worlds

Rooslawn's Unmapped Worlds