The dishwasher problem with crafting in games

I didn’t grow up particularly handy: the most I could do is know how to put together a computer, and only because that’s no different than playing with LEGOs. Almost as expensive, too.

As an adult, I’ve slowly gotten better at doing things with my hands. It started (very) slow. Patching a flat tire on my bike. Hanging pictures and shelves. Then my partner and I bought a house - and calling in tradespeople got expensive quick. I learned to do basic electrical work - light switches and outlets. I patched up drywall. Painted a room. Fixed a broken door jamb. Repaired stucco. Planted a tree. It’s not much for many, but these are huge steps for me.

Last month was the pinnacle of my handiness: our dishwasher started leaking water, and I was quoted $600-800 for a repair. That’s a lot of money for a leaky dishwasher. So I found some YouTube videos, printed out the manual, pulled the bastard out from under the counter, and after two days, a trip to the hardware store, and $10 later - I managed to replace the leaky grommet. I was extremely proud, because even the tutorials and the manuals recommended I replace the whole assembly, which costs hundreds of dollars and is backordered for months. But I figured out what was wrong, I fixed it on a cheap-cheap, and the dishwasher since has been going strong.

I felt on top of the world.

Right, video games. Here’s the problem with crafting systems in games: despite how much crafting systems have evolved - they don’t really get close to replicating that feeling of mastery, of ingenuity - of you figuring something out as you make something out of nothing. Yes, fixing a dishwasher and crafting a sword aren’t exactly the same thing - but they share the same core: understanding something well enough to work on it with your hands.

Yeah, yeah, I know we’re talking about games - but if games can make me feel a whole wide range of emotions, if games can make me care about imaginary companions and made up worlds - there’s no reason for crafting to feel so… dull.

The feeling is off

Games often default crafting to menus. “Click here to smith a dagger” is not a particularly tactile activity, nor is it an engaging game mechanic. Game designers often combat this by introducing mini-games: Wartales has a very simple mini-game where you have to click on pieces of metal at the right moment when crafting. It keeps me engaged for a few seconds, and the piece’s quality depends on the timing. It’s a tiny step - like me hanging a picture on the wall - but it’s a step in the right direction.

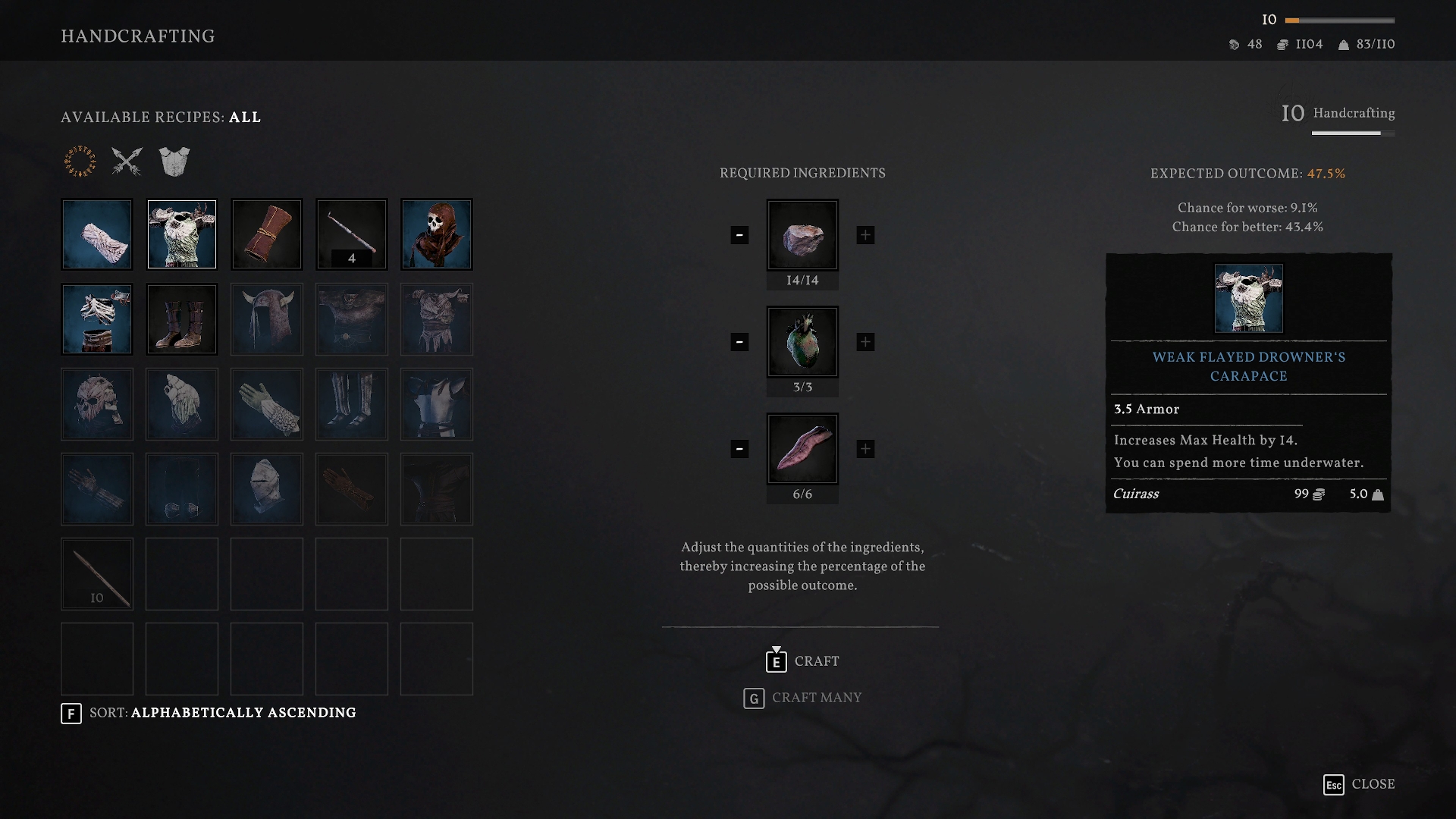

Tainted Grail: Fall of Avalon borrows the crafting system from The Elder Scrolls games (or any other recent open world game). There’s a tiny improvement here - your skill, combined with the volume of materials you use, dictates quality of the output. Still, it’s just a menu to click through.

Tainted Grail: Fall of Avalon borrows the crafting system from The Elder Scrolls games (or any other recent open world game). There’s a tiny improvement here - your skill, combined with the volume of materials you use, dictates quality of the output. Still, it’s just a menu to click through.

Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild makes cooking feel satisfying by having you throw a bunch of ingredients in the pot and watching them bounce around. There’s a very satisfying ta-da sound at the end, too. It feels nice - and we’re not even yet talking about meaningful rewards like increased health, attack power, or element resistance.

My favorite examples of the way crafting systems feel are Vintage Story and Valheim.

Vintage Story transitioned its crafting into the third dimension. To create a spearhead, you knap flint - breaking off pieces one by one until the spearhead is shaped. To make a pot, you have to shape it from clay, piece by piece, and then fire the result in the kiln. To smith a knife, you heat a bar of metal, and strike it in different places to move the material around the blade.

And the game designers’ decision pays off: as I play, I remember firing every crockpot I use. I cherish my handmade pickaxe, I remember how much love went into crafting my scythe, and I proudly display my blacksmithing hammer when it’s not in use.

This is what a lot of early game looks like in Vintage Story: knapping flint, one tiny block at a time. It’s a really tactile experience which connects you with the world.

This is what a lot of early game looks like in Vintage Story: knapping flint, one tiny block at a time. It’s a really tactile experience which connects you with the world.

Crafting in Valheim is less tactile - you click in a menu, you get an item - but the crafting stations, and the way they interact is immersive. Your workbench needs to be under a roof. If you want to smith something, an anvil must be nearby. A skinning rack in proximity is needed if you want to work with leather. It feels like your little viking workshop is a real place.

The grind

I remember crossing into the Black Forest in Valheim for the first time. After fighting off a horde of new enemies and exploring the area, I stumble upon a copper vein. I’m ecstatic, my brain is racing on what my new find could unlock - oh the possibilities! So I whip out my shoddy pickaxe and strike the earth. I attract some angry dwarfs, deal with them, and get my first piece of copper ore. I feel incredible.

I mine a couple more pieces of ore, head back to my base, pull up the crafting menu - and learn that I need like 200 more copper pieces to make everything I want. Ugh.

I head back, and I mine, and mine. Fill up the inventory, run back to the base, repeat. You get a cart to make your life easier, but it isn’t easy enough. The mine and the base are both near the coast, so I sail between them on my little Viking ship. Over and over again. I went from discovering the new world to running a ferry.

Valheim: running the same route, over and over again. It’s tedious.

Valheim: running the same route, over and over again. It’s tedious.

I get what the designers were going for. Making you sail the ore home is supposed to feel like an expedition - you’re a Viking, after all, hauling your spoils across dangerous seas. And the first time? It does feel like that. The ocean is scary, the wind is against you, there might be a serpent. But by the fifth trip, I’m not a Viking on an expedition. I’m just Peter, stuck in a commute.

In hindsight, after getting further into the game - I did realize that instead of stubbornly ferrying materials, I probably should’ve built a small mining outpost to process materials on site. And I did that later on, and it was indeed easier, and more fun. I’m still annoyed though, even if it was entirely my own fault.

Subnautica handles this better, though not perfectly. It rarely asks for more than a handful of any given material, and when it does need something in bulk, the gathering itself has some decision making involved. Do I risk bringing my Seamoth deeper than it can safely go? (Yes, I should) Do I build a small outpost near the resource deposit? Is it worth crossing through Reaper Leviathan territory for a shortcut? (No, it wasn’t) The ocean doesn’t stop being dangerous just because you’ve been there before, and that tension carries the repetition in a way that Valheim’s tenth boat ride just doesn’t.

But even Subnautica isn’t immune. Late asks for a lot more materials: by then I already know where everything is, I’ve mapped out all the safe routes, and the gathering just starts to drag. I’m just going through the motions. I replay Subnautica every couple of years, and I stop playing every time I get into the late game.

You need lots of materials as you engage in late game activities, including building. The game drags down during the resource runs.

You need lots of materials as you engage in late game activities, including building. The game drags down during the resource runs.

The games that actually solve the grind tend to lean into automation. Factorio is the obvious example - the whole game is about building machines that do the gathering for you. You never stop needing more iron. But the satisfaction shifts from “I collected the thing” to “I built a system that collects the thing, processes the thing, and delivers the thing exactly where it needs to go.” A factory must grow: there’s a satisfying gameplay loop here. My spaghetti monster of a factory processes more ore in a nanosecond than I could mine by myself in an hour.

When a game asks you to farm a material by hand for hours, it’s telling you something about itself: the gathering wasn’t designed to be fun on its own. And that’s fine, if the game gives you a way around it. But when it doesn’t - when it just expects you to keep making the same boat trip - that’s when I start thinking about what else is in my backlog.

The loot problem

Here’s a design trap that I think about a lot: what happens when a game has both crafting and loot?

In Skyrim, smithing wins. Level it up and you can make gear that outclasses almost anything you’ll find in a dungeon. Which sounds great until you realize what it costs you - the excitement of finding something. Why care about a chest at the end of a dungeon when your handmade dragonbone sword is already better than whatever’s inside?

The alternative is worse though. If loot is always better than what you can craft, then crafting is a waste of your time. A trap for players who don’t know better. “Thanks for spending six hours leveling blacksmithing - this sword that a bandit just poked you with is better than anything you could ever make.” Tough luck.

And if they’re roughly equal, crafting just feels redundant. Why have the system at all?

Being improperly geared for a fight in Monster Hunter: World is the fastest way to die.

Being improperly geared for a fight in Monster Hunter: World is the fastest way to die.

There’s really only one exit, and it’s to stop crafting and loot from competing. Make them do different things. Monster Hunter gets this - you’re not crafting “better” armor, you’re crafting armor that changes how you play. Fire resistance for the fire dragon. Poison resistance for the poison one. Your crafting choices are preparation and strategy, not just climbing a power ladder. I still remember making my first fire-resistant set before fighting Rathalos and feeling like I’ve actually prepared for something.

Guild Wars 2, with its famously horizontal progression system, lands in a similar place where crafted gear is about self-expression through stat combinations and specialized builds, not raw power.

I think the way around the loot problem is sidestepping it with sidegrades: expanding what you can do, opening new options, or providing avenues for self-expressions - and not just making the number go up.

The recipes suck

Here’s where my dishwasher comes back in. The manual told me to replace the whole pump assembly. The YouTube videos agreed. But I looked at the thing, figured out it was just the grommet, and fixed it my way. The solution wasn’t in any guide. I had to get to it on my own, which - despite having a chance of not working, or likely because it had a chance of not working - was immensely satisfying.

Many crafting systems don’t let you do that. You open a menu, you see a list of things you can make, and you pick one. The output is predetermined. Combine iron ingot and leather strip - you get an iron dagger (“you’re finally awake”). Every time. The same iron dagger everyone else gets. There’s no room for ingenuity, no moment where you think “what if I tried this instead?”

The games that break out of this are the ones that give you components and rules instead of recipes.

Tears of the Kingdom’s Ultrahand is the obvious recent example. You can stick almost anything to almost anything, and the physics engine decides if your creation works. There’s no “combine wheel plus plank plus fan equals car” recipe. Players built flying machines, walking mechs, automated turrets - things the designers never anticipated. The system hands you materials and physics and says “figure it out.” Ultrahand gets a bonus point for making it a tactile, in-world experience - you’re reaching out and grabbing things, not navigating a menu.

This is Tahriel: He has discovered that you can fortify your acrobatics skill by a thousand points. The landing was a bit of an afterthought, unfortunately.

This is Tahriel: He has discovered that you can fortify your acrobatics skill by a thousand points. The landing was a bit of an afterthought, unfortunately.

Morrowind’s spell crafting is an older example of the same idea (did you think I could write an essay without bringing up Elder Scrolls at least a few times?). The game gives you spell effects, magnitudes, durations, and areas - and you combine them however you want.

You could make a spell that fortifies your acrobatics by a thousand points for one second and launch yourself across the entire map. I remember feeling real smart when I figured out that I can combine a weakness-to-fire effect with fire damage to make a fireball spell which hit ridiculously hard. Or how I managed to enchant some armor to make me permanently invisible through stacking Chameleon effect - something I’m still proud of over twenty years later. The system gave you components and constraints, and what came out the other end was invention. Not “pick from column A and column B” - actual, sometimes game-breaking invention. Bethesda quietly removed spell crafting from later Elder Scrolls titles, and I’ve never stopped being annoyed about it.

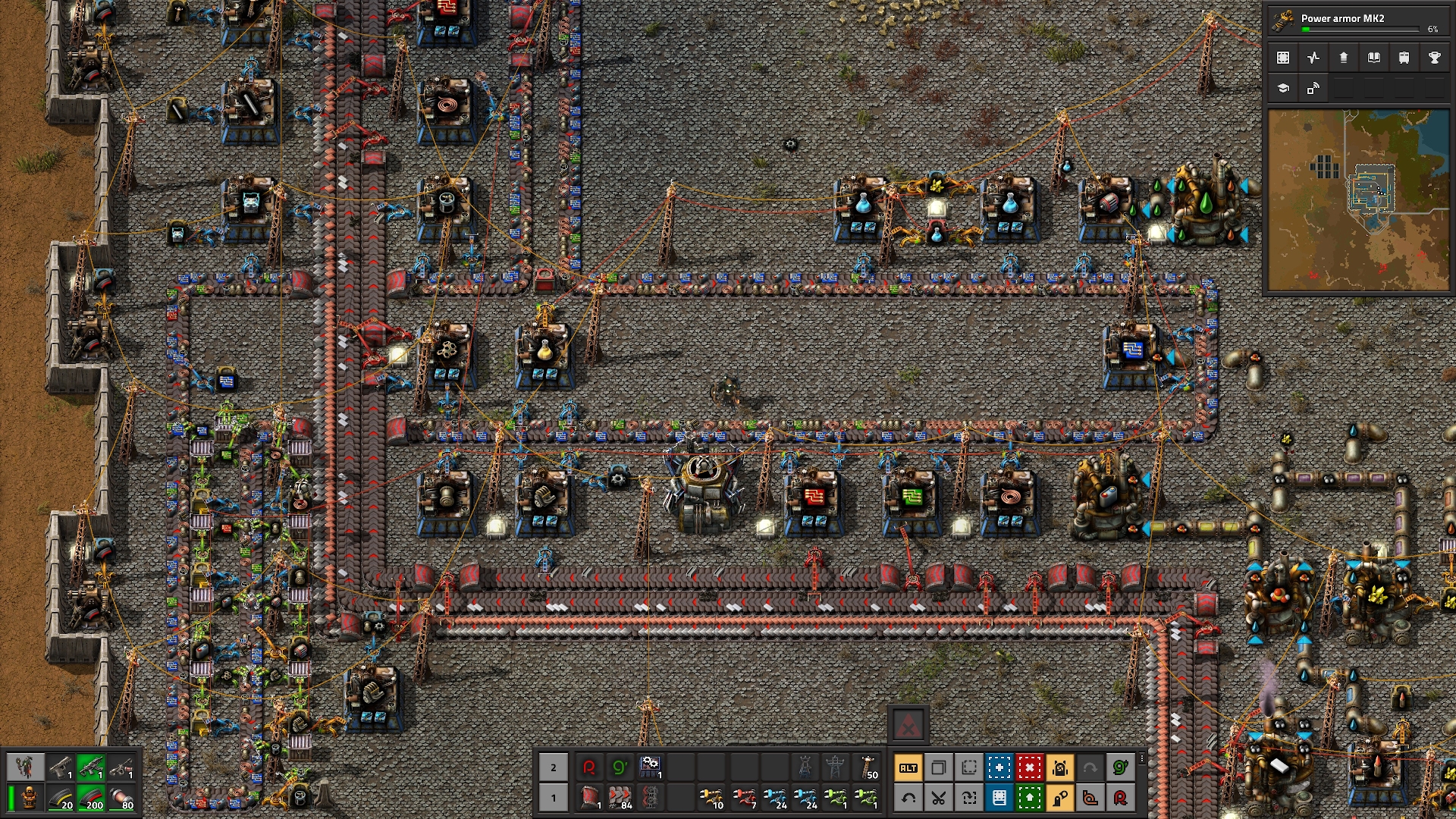

Factorio belongs here too, not just in the grind section. Yes, it solves the gathering problem through automation - but the factory you build is itself a creative act. There are input-output ratios you have to satisfy, but how you arrange it all, how you route your belts and balance your production lines - that’s yours. And by design, there’s almost no single optimal way to do it, which leaves you infinite room for messy creativity. No two players’ factories look the same, because the game gives you constraints and tools, not blueprints.

Witness my pipes, belts, assemblers, and wires: it’s a bit of a mess, but it’s uniquely my mess and I’m proud of it.

Witness my pipes, belts, assemblers, and wires: it’s a bit of a mess, but it’s uniquely my mess and I’m proud of it.

Dwarf Fortress is similar once you get into its mechanisms and traps. You can link pressure plates to bridges, attach weapon traps to hallways, design elaborate systems that redirect water or magma. Your fortress’s defenses are a crafted thing, and nobody designed them but you. The game gave you gears and levers and let you figure out the rest. I lost many a fortress to an overly elaborate mechanism that flooded the whole castle with magma. Stupid dwarves.

The best crafting systems hand you components, let you figure out how they interact, and get out of the way. You get rewarded for understanding a system well enough to make a thing developers may not have exactly planned for.

Other people

Let’s talk about MMOs for a second, because they show something about crafting that singleplayer games just can’t.

In World of Warcraft, crafting always felt like an afterthought to me. You level it up because you feel like you should. You make some things. Most of them are worse than dungeon drops by the time you can actually craft them. It exists, it has recipes and materials, but it doesn’t really feel like it matters to anyone - including you. I did my share of tailoring, leatherworking, and blacksmithing across a few expansions - and I can’t remember a single thing I made. Not a single item.

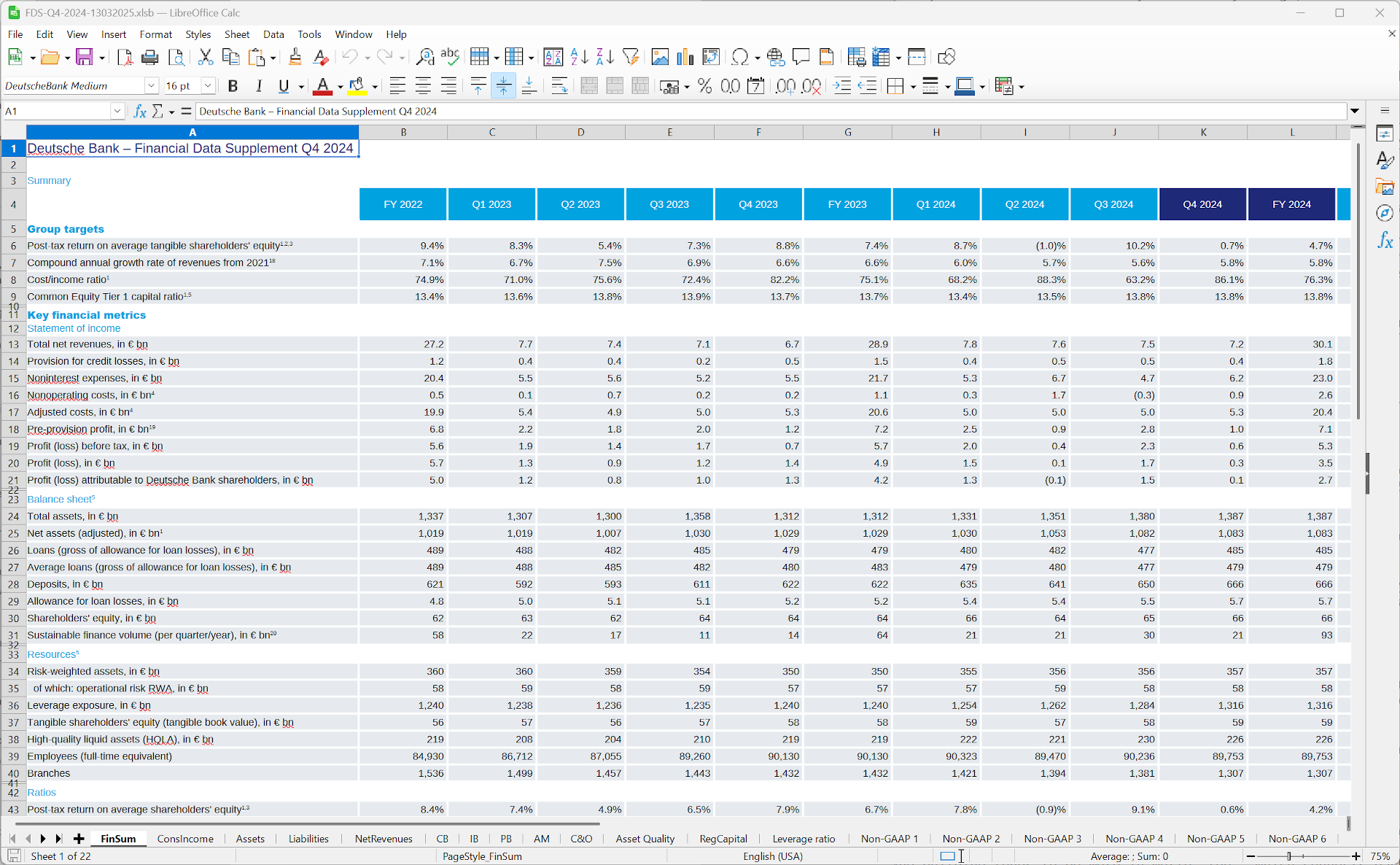

Now think about Eve Online. In Eve, almost every ship, module, and bullet was made by a real player. Someone gathered the materials, ran them through production, put the result on the market. When someone else buys that ship and flies it into a war and loses it - it’s gone. Destroyed. And it needs to be replaced. By another player. There’s a whole supply chain of real people making real things for other real people, and the things they make get used up, blown up, and need to be made again.

Eve Online: If you look closely, you may notice this is a screenshot of Deutsche Bank financial report for 2024. It’s the same thing.

Eve Online: If you look closely, you may notice this is a screenshot of Deutsche Bank financial report for 2024. It’s the same thing.

When I fixed my dishwasher, the satisfaction wasn’t just in the fixing - it’s that my family uses it every day. I get to smile a little when I hear it running and the water stays inside where it belongs. The thing I repaired matters because people depend on it. Eve’s crafting works for the same reason - someone out there needs the thing you made, and when it’s gone, they’ll need another one.

Old School RuneScape sits in a weird middle ground - the act of crafting, just like the whole game, is mind-numbingly repetitive (click, wait, click, wait), but the player economy gives the results meaning. Someone buys what you made. It circulates. The making is boring, but the made thing goes somewhere.

Singleplayer games have to work harder at this since there’s no other player on the receiving end. And honestly, most of them don’t pull it off - you craft things that go into your inventory and sit there, or get vendored, or get replaced by the next tier of things you craft that also go into your inventory. The games that avoid this feeling are the ones where your crafted thing changes your world in a way you can see and feel. Your Valheim workshop is a place you walk through every day. Your Vintage Story tools feel like yours because you shaped them by hand. Your Tears of the Kingdom contraption solved a problem in a way nobody else’s did. These things have presence, even without another player to hand them to.

Where crafting meets building

I’ve been talking about crafting as if it’s separate from building, but the line is blurrier than I’m pretending. Is building a house in Minecraft crafting? You’re combining materials. You’re making decisions. The result is a thing that exists in the world and reflects your choices.

Minecraft: It’s in the name.

Minecraft: It’s in the name.

I think crafting gets more interesting the closer it moves toward building - the closer it gets to expressing something rather than following a recipe to get an output. The crafting table in Minecraft is boring (and even more boring since the recipe selector got introduced post-beta). The house you build with what comes out of it is not.

Lines get even more blurry when you consider Minecraft’s redstone - game’s built-in “programming language” which lets you create elaborate contraptions as the builds move beyond aesthetics.

Tears of the Kingdom’s Ultrahand, Factorio’s factory design, Dwarf Fortress’s trap systems - these all sit on that messy line between crafting and building. You’re not making a thing from a list. You’re designing, testing, watching it fall apart, rebuilding. There’s no recipe.

And building tends to be more in-world, too - which connects back to why the feeling matters. You’re not navigating menus; you’re placing things in a space, walking around them, interacting with them physically. Valheim’s workshop requirement - workbench under a roof, anvil nearby, skinning rack within reach - that’s crafting bleeding into building bleeding into inhabiting a place. The more a crafting system asks you to exist in the game’s world rather than in its UI, the better it feels.

Maybe the line between crafting and building doesn’t matter that much. As I’m editing this piece, on a Sunday night, I can hear the hum of my dishwasher. Every time I hear that little whir, I feel a moment of pride. That’s what I’m looking for in my games.

Rooslawn's Unmapped Worlds

Rooslawn's Unmapped Worlds