On owning games

For the past couple of weeks, I’ve been working on compiling my thoughts on every PC Game Pass game I’m familiar with. That 10,000-words-so-far monstrosity is likely coming next week, but it did get me thinking about owning games.

PC Game Pass makes it absolutely clear that these aren’t the games you own - and that being on PC Game Pass is a timed deal. Which is fine - it’s a subscription that clearly advertises itself as such. PlayStation Plus is a similar deal. And streaming is a trend inescapable in film, television, and music - so what’s the big deal?

The subscriptions aren’t a big problem. Buying games is.

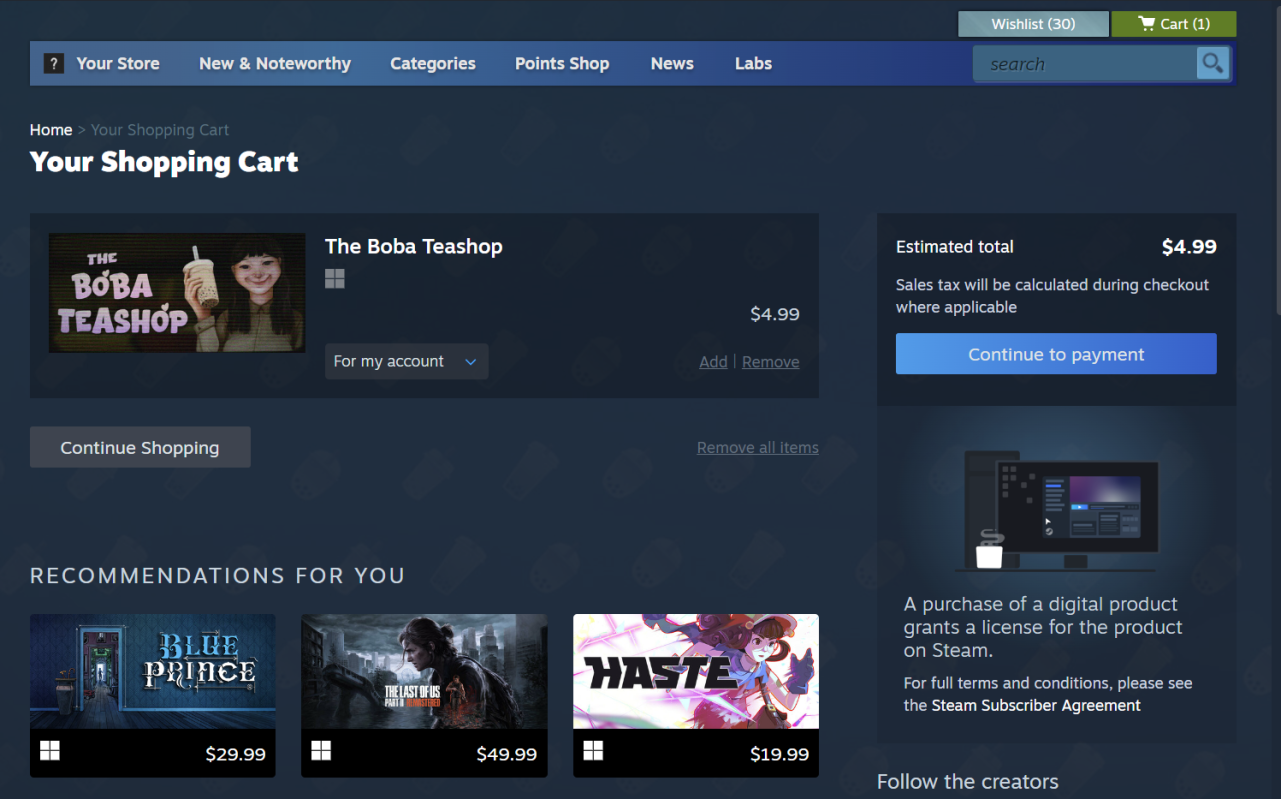

Last year I was buying yet another game on Steam - and a little side panel came up telling me, in plain English, I don’t own the games I buy - I’m only purchasing a license to play them. Now, this wasn’t really a change of heart from Valve; the Steam subscriber agreement always made it clear you don’t own your purchases. The pop-up was triggered by California’s AB-2426 bill, which requires digital storefronts to disclose if hitting the “Buy” button doesn’t actually grant you “an unrestricted ownership of a digital good.” And this was a good reminder that the 500-or-so titles sitting in my library aren’t really mine.

Valve: A purchase of a digital product grants a license for the product on Steam.

Valve: A purchase of a digital product grants a license for the product on Steam.

As an aside, I do appreciate the direction in which California consumer protection is moving (hello, California Consumer Privacy Act and The Right to Repair).

Yup, for all of these games, you’re holding a license to play them, and you’re reliant on Valve to keep up their end of the bargain. Now, historically, Valve has been trustworthy in that regard, but times change, and so do organizations. And there were instances when Valve removed games directly from users’ libraries upon publisher request.

This is equally true for games “bought” on digital storefronts like the Microsoft/Xbox Store, PlayStation Store, Nintendo Store, or any others. Fun fact, even the games you purchase on disks merely give you a license to play the game, and the publisher reserves the right to pull the license at any point. It’s much harder and more painful for them to do so with physical media, though. I imagine the license approach is there to make sure you don’t go around copying and distributing the game, but I’m not a lawyer - what do I know.

Blockchain technology was (and is still, thankfully with less hype) promising to offer a better way to own digital content, but we’re yet to see meaningful progress to replace the license-based approach (don’t worry friends, I’m not here to peddle NFTs). While publishers voiced interest in leveraging blockchain in their business strategies, there weren’t any concrete plans laid out. And a blockchain implementation that’s valuable for consumers - that is, the ability to verify and transfer true ownership (rather than a license), similar to what you might have with physical media - would likely eat into the publishers’ profits.

So, what if you wanted to preserve a game you bought? A game you’d like to feel like you own?

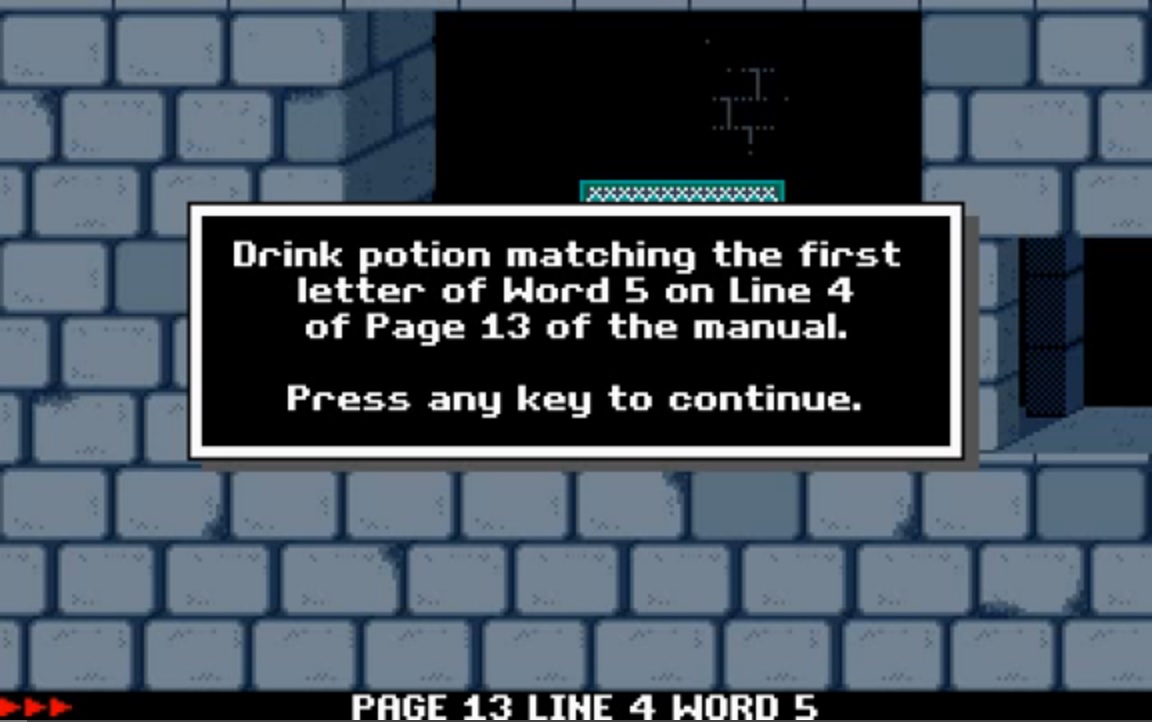

An example of an early DRM in Prince of Persia (1990). Image taken from Everything is Bad for You.

An example of an early DRM in Prince of Persia (1990). Image taken from Everything is Bad for You.

Just buy the disks, right?

This used to be true, but these days, there are many instances of single-player and offline games with DRM that verifies your license against the publisher’s services. DRM stands for Digital Rights Management, and it’s something that’s been around since the mid-80s in different forms, shapes, and sizes. Essentially, DRM is a way to make sure content isn’t easy to copy and distribute. For instance, really old games used to ask you to type a phrase from a certain page in a manual. Then there’s offline DRM, which might match a serial number from the disk to a predetermined hash. What’s more prevalent today, though, is DRM that requires an initial connection to the Internet to verify the purchase against a digital storefront or a publisher’s website – Steam DRM is a good example. And then there’s the infamous always-on DRM, which only makes the game playable when it’s connected to the Internet. Diablo III is one of the more popular recent examples of that.

I don’t like that, I don’t like that at all.

So you can buy the disks, and you get to “own” it as long as the DRM doesn’t rely on an Internet connection. Unfortunately, this information isn’t particularly easy to find upfront (although you can sometimes look up online what DRM system is used by the game), but that’s a start.

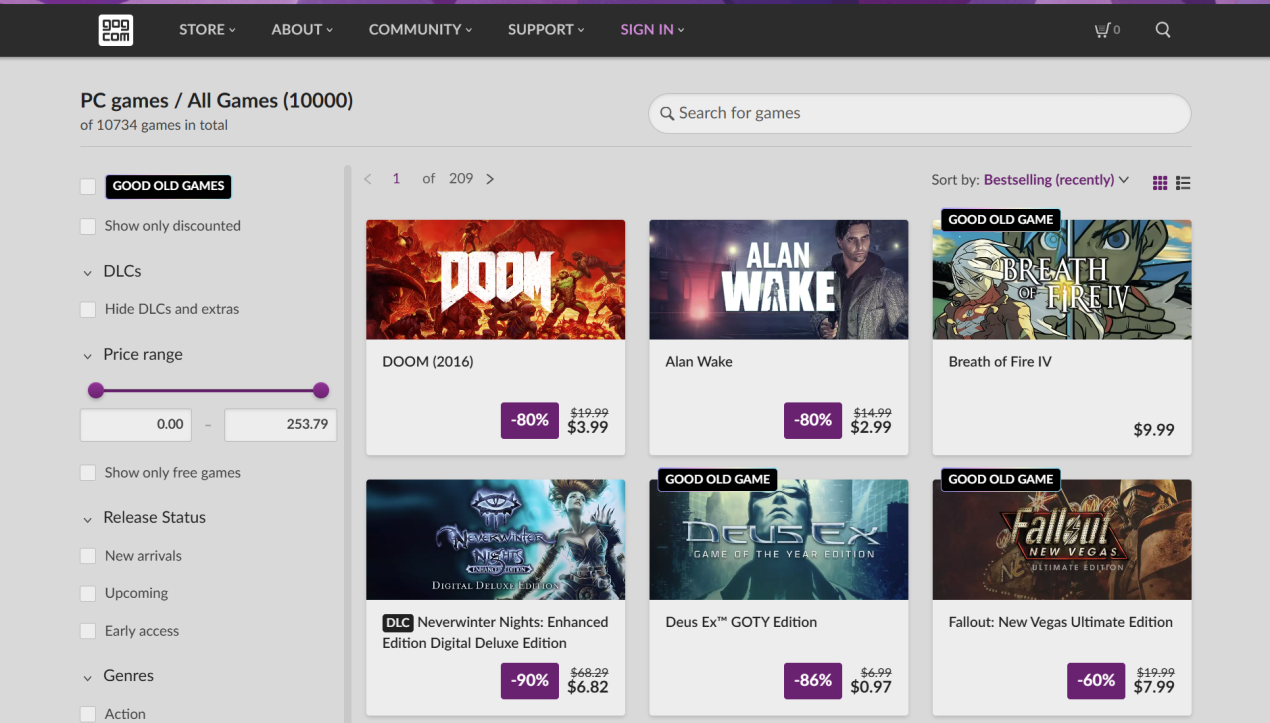

Good Old Games tagline reads: “Best video games, DRM-free”.

Good Old Games tagline reads: “Best video games, DRM-free”.

For digital-only games, the situation is a bit more bleak. But there is a light at the end of the tunnel: Good Old Games. The Good Old Games store (GOG, for short) sells all its games DRM-free as a guiding principle. While primarily focusing on older titles, new releases have been finding their way to the GOG storefront too. Humble Bundle sells most games with some form of DRM, but it does have the Humble Vault – a list of 50-100 DRM-free indie titles you can download and keep if you subscribe to their service for at least one month. However, the Vault hasn’t been updated with new titles in a while and doesn’t seem to be a priority for the storefront, unfortunately.

You can download DRM-free games and save them to storage of your choice. That game’s mostly yours forever, barring future compatibility issues.

Interestingly enough, games on Steam (and allegedly other storefronts) can choose to ship without any DRM. This means that after you download them, they’re effectively yours – you can decouple them from Steam by moving the game files to other storage media. Baldur’s Gate III is one of the titles that famously ships without DRM. But you do have to test each title. A common way to check if a title is DRM-free is by closing Steam, disabling the internet on your device, and then trying to launch the game’s executable directly from its folder. If Steam launches, the game uses Steam DRM. If the game fails to launch but Steam doesn’t pop up, it likely uses some other DRM system. If the game launches fine, then it might be DRM-free. Try moving its installation folder elsewhere and launching it again to be more certain.

So yeah, it’s a bit of a mess, isn’t it? The dream of a digital library that’s truly yours feels further away than ever for most games. It kinda makes you think twice before hitting that ‘Buy’ button, knowing you’re mostly just renting indefinitely. For me, it means I’m definitely leaning more towards GOG or hunting down those DRM-free gems on Steam when I can. It’s not perfect, but hey, at least it’s something, right? Maybe one day, ‘owning’ a game will actually mean owning it. A gamer can dream.

Comments

Respond directly on Bluesky (threads shown below) or Medium (view comments there).

Rooslawn's Unmapped Worlds

Rooslawn's Unmapped Worlds