I want your game to not care about me

I like feeling small. Not in the sad, pathetic way - in the cosmic way. That very specific flavor of dread where you realize you’re an utterly meaningless speck in a vast, uncaring universe. There’s something weirdly comforting in it, actually. When you internalize just how incomprehensibly huge existence is, your own problems start to feel a lot smaller. Life’s got you down? Sure, but also there are forces beyond mortal comprehension out there, so maybe it’s fine.

I remember the exact moment Subnautica begun messing with my head. I’d been swimming down, chasing some resource or another, and I looked up. No sunlight. Just dark water above me, dark water below me, dark water in every direction. I was alone on an alien planet, suspended in an ocean that couldn’t care less whether I lived or died. My lizard brain screamed at me to surface, to find light, to get out. I didn’t want to keep playing. I had to keep playing.

That’s the feeling. That’s what I’m chasing.

Subnautica: Shout out to the time I was at the bottom of the ocean, scavenging through an abandoned research outpost, only to be greeted by this. The pants were shat.

Subnautica: Shout out to the time I was at the bottom of the ocean, scavenging through an abandoned research outpost, only to be greeted by this. The pants were shat.

Books absolutely nail this. Lovecraft and the stories inspired by his work expertly deliver that “horrors beyond comprehension” vibe. I’m a huge fan of Peter Clines - if you haven’t read 14, do yourself a favor. It’s about an apartment building where things are just not quite right. Doors that shouldn’t exist. Sounds from empty rooms. A creeping wrongness that builds until you realize the wrongness goes all the way down. It’s unsettling in all the best ways.

Games, though? Games struggle. And if you think about it for even a second, it’s obvious why.

The agency problem

Here’s the fundamental tension: games are built around player agency. You make choices. You affect the world. You matter. Because otherwise - well, otherwise you could just read a book or watch a movie. But cosmic horror is built on the opposite premise - you don’t matter. You never mattered. The universe operates on scales and timelines where your existence is a rounding error.

These two ideas are almost impossible to reconcile.

And here’s the thing most games get wrong: there’s a difference between feeling powerless and feeling insignificant. Survival horror makes you feel powerless - you’re vulnerable, under-resourced, hunted. But you still matter. The monster is chasing you specifically. Your survival is the point.

Cosmic horror is something else entirely. It’s not that the eldritch entity hasn’t destroyed you because it can’t. It’s that it doesn’t care to. You could smash that anthill outside your house, sure. Step on that bug crawling across your kitchen floor. But why bother? Maybe if you’re in a bad mood. Maybe if it’s in your way. The ant’s survival isn’t a victory against you - it’s just not worth the effort. Sorry, Gandhi.

That’s the vibe. That’s what’s so hard to translate into a medium where the player is, by definition, the center of the experience.

Space Marine 2 is is undoubtedly cool, but a power fantasy is about the opposite of making you feel insignificant. Which is fine, I do like slashing through waves of tyranids after all.

Space Marine 2 is is undoubtedly cool, but a power fantasy is about the opposite of making you feel insignificant. Which is fine, I do like slashing through waves of tyranids after all.

Take my beloved Warhammer. The lore is dripping with cosmic dread. The Chaos gods are locked in an eternal war against each other, and humanity is collateral damage - a psychic buffet and occasional entertainment. The tyranids are a galaxy-consuming swarm, and there’s a popular fan theory that what we’ve seen so far is just a scout fleet. The real hive mind hasn’t even noticed us yet, or maybe decided we’re not worth the energy. That’s terrifying stuff.

But boot up Space Marine or Space Marine 2 and you’re a seven-foot wall of ceramite mowing down hordes of enemies. The power fantasy is the point. You feel like a badass because you are one - and the cosmic dread evaporates the moment you realize nothing on screen is a threat to you. The lore says humanity is clinging to survival against incomprehensible forces. The gameplay says you’re an action hero.

I started The Sinking City with high hopes - it’s explicitly Lovecraftian, set in a half-drowned city full of fish people and eldritch secrets. And then the game handed me a club to fend off the unspeakable horrors. Not with difficulty, not with desperation - just click until dead. Sir, that’s not cosmic dread. That’s a beat-em-up. The second you can meaningfully fight back, you’ve undermined the whole premise.

The Sinking City: This eldritch entity becomes a lot less scary once you realize you have a shotgun for dealing with it.

The Sinking City: This eldritch entity becomes a lot less scary once you realize you have a shotgun for dealing with it.

We’ve got survival horror covered - the Resident Evil series has been doing that for decades. Psychological horror? Silent Hill, Amnesia, Penumbra - take your pick. But those are different flavors of fear. Survival horror is about resource scarcity and vulnerability. Psychological horror is about your own fractured mind. Cosmic horror is about the uncomfortable truth that it doesn’t matter what you do. The universe isn’t hostile. Hostile would imply it notices you.

So how do you make a game - an interactive medium predicated on player choice mattering - feel indifferent to the player?

Some games actually pull it off. Let’s dig into how.

The ocean doesn’t care about you

Subnautica is a masterclass in cosmic insignificance.

You’re the only person on this entire planet. The ocean is deep and vast, and it doesn’t care about you at all. Not in a “the enemies want to kill you” way - in a “you are simply not relevant to anything here” way. The leviathans aren’t hunting you specifically. They’re just doing leviathan things. You’re food-sized, so sometimes they eat you. It’s nothing personal.

The first time you submerge deep enough that the sunlight disappears, something shifts. You’re not in a video game anymore. You’re in an environment that existed before you crashed here and will exist long after your oxygen runs out. And then you see them. The leviathans. Creatures so massive that your little seamoth submarine might as well be a pool toy. You build a Cyclops - a proper submarine, big and armored. It took hours to gather the resources. You feel safe now. Protected.

Subnautica: I sincerely hope whatever creature wore this skeleton is extinct. That thought is scarier than the ghost leviathan rushing at me right now.

Subnautica: I sincerely hope whatever creature wore this skeleton is extinct. That thought is scarier than the ghost leviathan rushing at me right now.

Then something hits you in the dark and your whole screen shakes and alarms are blaring and you realize: no, you’re not safe. You were never safe. You just made a loud burrito for the leviathans to enjoy.

The enormous skeletons you find - creatures even bigger than the leviathans you’ve been fleeing - raise the question: what else is out there? What killed those things?

And you’re in a dormant volcano, which is still somehow deep underwater. Approaching the edges of the crater and looking down into the void, into absolutely nothing, knowing that the ghost leviathans patrol those waters and they’re territorial and they don’t care that you’re just passing through. The deep ocean is like space, except you can’t see as well and everything wants to eat you.

That’s how you do cosmic dread. You don’t fight the ocean. You survive it, temporarily, until you don’t.

(Spoiler warning: Outer Wilds. If you haven’t played it, skip to the next section. Actually, close this article and go play it, I’d much rather you do that than read my stuff. By now you really should have played it. Okay, don’t say I didn’t warn you.)

Outer Wilds pulls off something similar, but with the cosmos instead of the ocean. You’re trapped in a 22-minute loop, and the sun explodes at the end of every cycle. Not because of anything you did. Not because of anything you can prevent. The star is dying. It was always dying. Your species, your solar system, your little archaeological project - all of it is a blip in a universe that was here long before you and will continue long after.

Outer Wilds: You’re not the first civilization to go extinct, although the death of the star will ensure no traces will be left for others to discover.

Outer Wilds: You’re not the first civilization to go extinct, although the death of the star will ensure no traces will be left for others to discover.

You can’t fight it. There’s no boss to defeat, no switch to flip. You can only understand. And understanding doesn’t save you - it just contextualizes your insignificance. The universe ends. You were there for a small part of it. That has to be enough.

Everything is already over

The Souls series approaches cosmic dread from a different angle. The horror isn’t tentacles and unknowable entities - it’s entropy (unless we’re talking Bloodbourne, then tentacles are also horror). Inevitable, universal decline.

In Dark Souls, the First Flame is fading. The gods are dying or mad or gone. The undead curse spreads. And you - the Chosen Undead - aren’t really saving anything. You’re delaying. Maybe. The game is genuinely ambiguous about whether linking the fire is salvation or just prolonging a dying age’s suffering.

Even if you “win,” you’ve just reset the cycle. Someone else will be in your position eventually, making the same hollow choice. The flame fades. Someone links it. It fades again. Forever, until someone doesn’t - and then it’s just dark.

Elden Ring takes this further with the Outer Gods - cosmic entities that view the Lands Between as a chess board. The Greater Will, the Frenzied Flame, the Rot God - these aren’t enemies you defeat. They’re forces operating on scales you can’t comprehend, and most of the game’s endings involve choosing which incomprehensible cosmic patron gets to shape reality next. You’re not the hero. You’re a piece being moved.

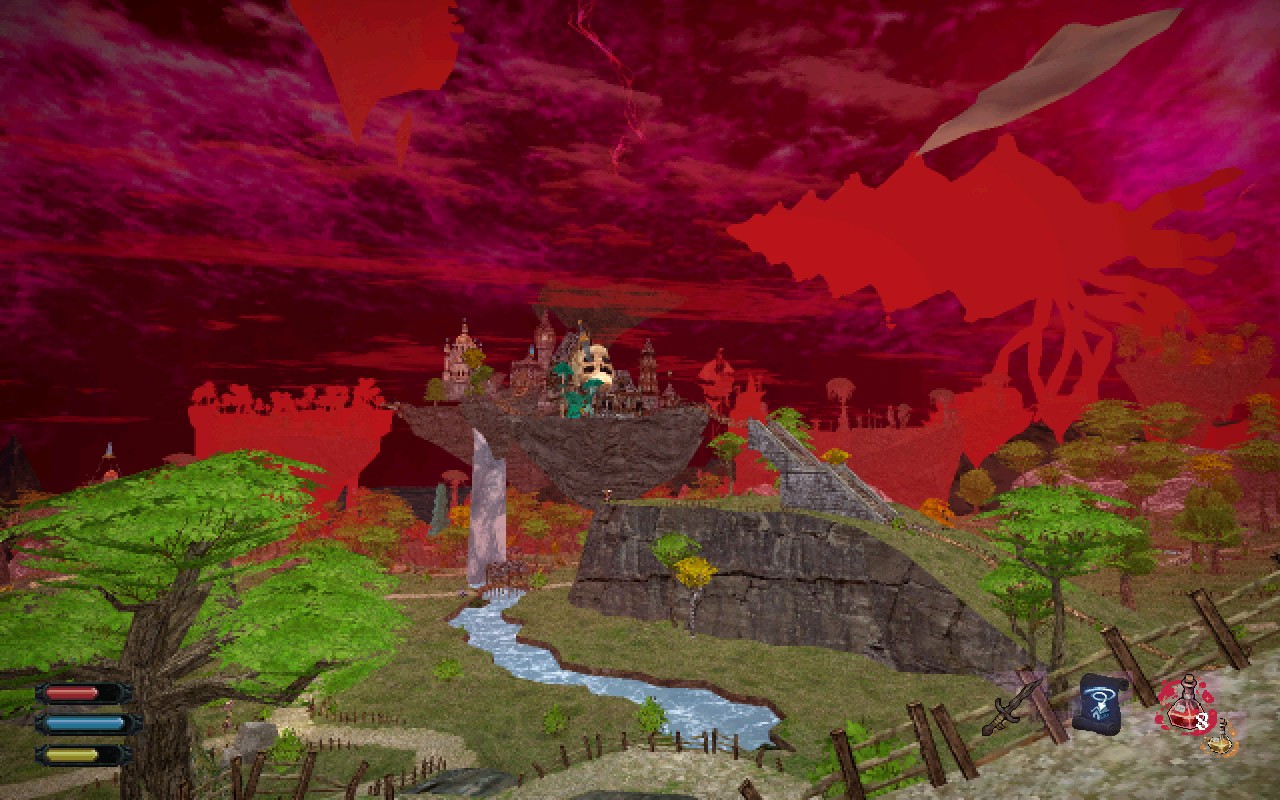

Dread Delusion: The gods are dead, and the new order is built upon their bones and corpses. Literally

Dread Delusion: The gods are dead, and the new order is built upon their bones and corpses. Literally

Dread Delusion literalizes this decay. The gods are dead. Not metaphorically - literally dead, their corpses rotting in the sky, leaking weird divine goo onto the fractured world below. Reality itself is coming apart at the seams. You wander through a world that’s already over, picking through the rubble of something that used to matter.

What makes these games work is that victory doesn’t fix anything. You can’t reverse entropy. You can’t make the dying world un-dying. You’re a participant in the decline, at best. A witness. The grinding continues whether you beat the final boss or not.

You don’t understand the rules

Then there’s Control, which shouldn’t work at all. It’s a third-person shooter. You have powers. You kill hundreds of enemies. By every metric, it’s a power fantasy.

And yet.

If you’ve spent any time on the SCP Foundation wiki, you know the vibe Control is channeling. I’ve lost hours to that site - it’s collaborative fiction about a shadowy organization that contains anomalous objects and entities. Some entries are creepy. Some are funny. Some are both. But the best ones share a common thread: the universe operates on rules we don’t understand, rules that make absolutely no sense, and the Foundation is basically janitors trying to keep reality from leaking through the cracks.

Control: Someone’s job is to constantly watch the fridge, or a terrible thing will happen. Why? The reasons are beyond mortal comprehension.

Control: Someone’s job is to constantly watch the fridge, or a terrible thing will happen. Why? The reasons are beyond mortal comprehension.

There’s something deeply compelling about that framing. Not heroes fighting evil. Just bureaucrats managing the incomprehensible. Filling out paperwork about a chair that kills you if you sit in it. Writing clinical reports on a stairwell that goes down forever. The banality makes the horror hit harder. Here’s form 419B describing the proper disposal procedures for an interdimensional toaster.

Control takes that energy and runs with it. The Oldest House operates on rules you don’t understand. Rooms shift. A fridge will kill everyone who stops looking at it, so there’s a guy whose job is just looking at the fridge. Oh yeah, and his shift change is late. Ouch.

The entity guiding you - the Board - speaks in overlapping, contradictory words, and you’re never sure if it’s helping you or using you or if those concepts even apply. You’re the director of the Bureau now, congratulations, here’s a service weapon, oh - your gun might be alive.

The tension doesn’t come from the combat. It comes from the creeping sense that you’re a pawn in something you can’t comprehend. You can clear a room of Hiss-corrupted agents, sure. But what is the Hiss? Where does it come from? What does it want? Can it want? The game gives you fragments, suggestions, redacted documents with more black bars than text. You never really understand. You just cope.

Skyrim: Each daedric lord has their own plane, which they care about a whole lot more than about the world. You don’t matter, the mortal world doesn’t matter.

Skyrim: Each daedric lord has their own plane, which they care about a whole lot more than about the world. You don’t matter, the mortal world doesn’t matter.

The Elder Scrolls does something similar, buried in its lore. The Daedric princes aren’t just powerful - they’re operating on motivations and timescales that mortals can’t grasp. And here’s the thing: they’re mostly preoccupied with each other. Their own realms, their own schemes, their eternal squabbles. Mortal affairs are petty distractions. When Mehrunes Dagon invades Tamriel, it’s not because he specifically hates you - you’re just there. And if you remember The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion, the player doesn’t stop the god’s advancement. Another god does. Yeah, you’re just there.

When Hermaeus Mora grants you forbidden knowledge, speaking to you like you’re a particularly interesting dust mote, it costs you nothing. And that’s almost worse. What does he get out of it? Why are you still alive?

The Daedra treat mortals the way we treat our games.

Think about Rimworld. Today you’re benevolent. Tomorrow you’re running an organ-harvesting colony where prisoners get turned into hats (extremely profitable, by the way). Or maybe you just never boot up the game again. Your colonists don’t know their existence depends on your mood and your schedule.

That’s us. We’re the colonists.

At their mercy

The most effective cosmic dread might come from the smallest moments - the ones where you genuinely have no idea what will happen next.

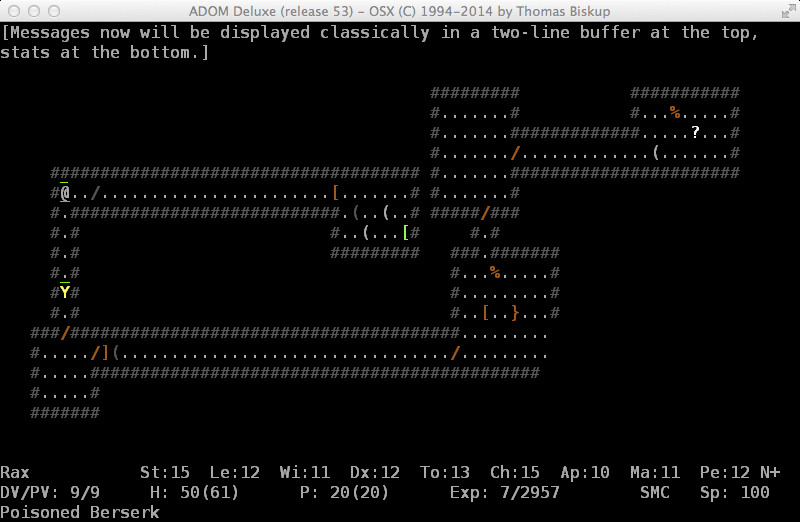

ADOM is an old-school roguelike from 1994, and it’s one of the most brutally unforgiving games I’ve ever played. If you’re not familiar with the genre, roguelikes are dungeon crawlers with permadeath - when you die, that’s it, your character is gone, your progress is erased. No saves. No do-overs. The genre has exploded in recent years with games like Hades, Dead Cells, and Slay the Spire, but ADOM is one of the originals that inspired them all. It’s ASCII graphics and keyboard commands and dozens of ways to die that you won’t see coming until they’ve already happened.

Ancient Domains of Mystery, or ADOM for short. Simple ASCII graphics hide layers of complexity, including an ability to make a plead to the gods.

Ancient Domains of Mystery, or ADOM for short. Simple ASCII graphics hide layers of complexity, including an ability to make a plead to the gods.

When everything goes wrong in ADOM - and in roguelikes, everything eventually goes wrong - you can pray. Begging your chosen god for divine intervention. And here’s the thing: you don’t know what will happen. The god might heal you. Might smite you. Might do nothing. Might do something weird. It depends on your standing with them, on cosmic alignment, on factors the game doesn’t explain. You can’t reload. You can’t look up the “right” choice because there isn’t one. You just pray and hope and accept whatever comes.

That’s the essence of cosmic horror. Not tentacles (unless you’re playing Bloodbourne). Not scary monsters. The acknowledgment that you’re at the mercy of something bigger than you, and your understanding or agreement isn’t required.

What actually works

Looking at what works, there are some common threads. Scale helps - something so vast your actions feel proportionally tiny. Systems that would be doing their thing whether you showed up or not. Rules that don’t make human sense. And crucially: no real victory. You can survive, delay, understand. But you can’t win against entropy. The best you get is meaning within the meaninglessness. A campfire before the sun explodes.

That last part is probably why most games don’t even try. We want players to feel accomplished. We want endings to feel earned. Cosmic dread asks for the opposite - acceptance that all victories are local and temporary. That’s a hard sell.

I don’t know if there’s a solution. Maybe it’s just an inherent tension. Games are about mattering. Cosmic horror is about not mattering. Maybe you can’t fully reconcile those.

But I keep chasing that feeling anyway. Swimming alone in an alien ocean. Actually, booting up Subnautica to find that earlier screenshot made me want to replay the game - off I go.

Comments

Respond directly on Bluesky (threads shown below) or Medium (view comments there).

Rooslawn's Unmapped Worlds

Rooslawn's Unmapped Worlds