Fast travel is awesome

Get your pitchforks here! Come get your pitchforks! “Fast travel is awesome.” Okay, I omitted a word for dramatic effect: “Diegetic fast travel is awesome”. That is, fast travel that’s deeply integrated with the game’s world is among the most rewarding in-game mechanics.

Let’s start with my absolute favorite example. Morrowind.

That overgrown flea is called a silt strider in The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind. For a modest fee, it’s master will take you between some of the game’s cities.

That overgrown flea is called a silt strider in The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind. For a modest fee, it’s master will take you between some of the game’s cities.

Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind has many in-game fast travel systems - at least 7. You might be familiar with a few, if you’re a casual player - there are the silt strider - the huge flea-like beasts of burden that ferry you across some cities. There are ships that can take you across the coastal towns. Major towns all have a mages guild, which are connected by the teleport network. If you’re adept at mysticism, you may have used mark and recall - spells which let you “remember” a single spot and teleport to it later.

We’re already up to three travel networks (and one specific spell). These travel network have some overlap - but to travel effectively you need to utilize all of them. You may take a boat from one coastal settlement to another, followed by a silt strider, followed by a mage guild teleport. Which is hell of a lot faster than walking, and makes you feel good about knowing the game’s geography - since you’re saving yourself so much trouble.

You see, Morrowind is mostly a game about navigation. The majority of the game’s quests are simple fetch quests, and the complexity comes from having to actually find and then navigate to the subject of the quest. It’s the kind of a game that gets ruined by guides very easily, because figuring out whom to talk to, where to go, and how to get there are 90% of the game’s mechanics. So figuring out a way to turn a 30 minute trek through the wilderness into a couple of minutes of taking Vvardenfell’s public transit feels like an incredible achievement, a true mastery of one of the game’s systems.

But wait, there are more fast travel systems in Morrowind. The Tribunal Temple is prevalent on one side of the island, and an “Almsivi intervention” spell lets you travel to the nearest temple. Only some cities have temples, and which are concentrated on one side of the island. There’s the Imperial Cult prevalent on the other side of the island, and “Divine intervention” will teleport you to the Imperial altars. If you’re willing to put in the work, the ancient Dunmer of the island have set up a propylon network across the island’s strongholds, which require keys to unlock.

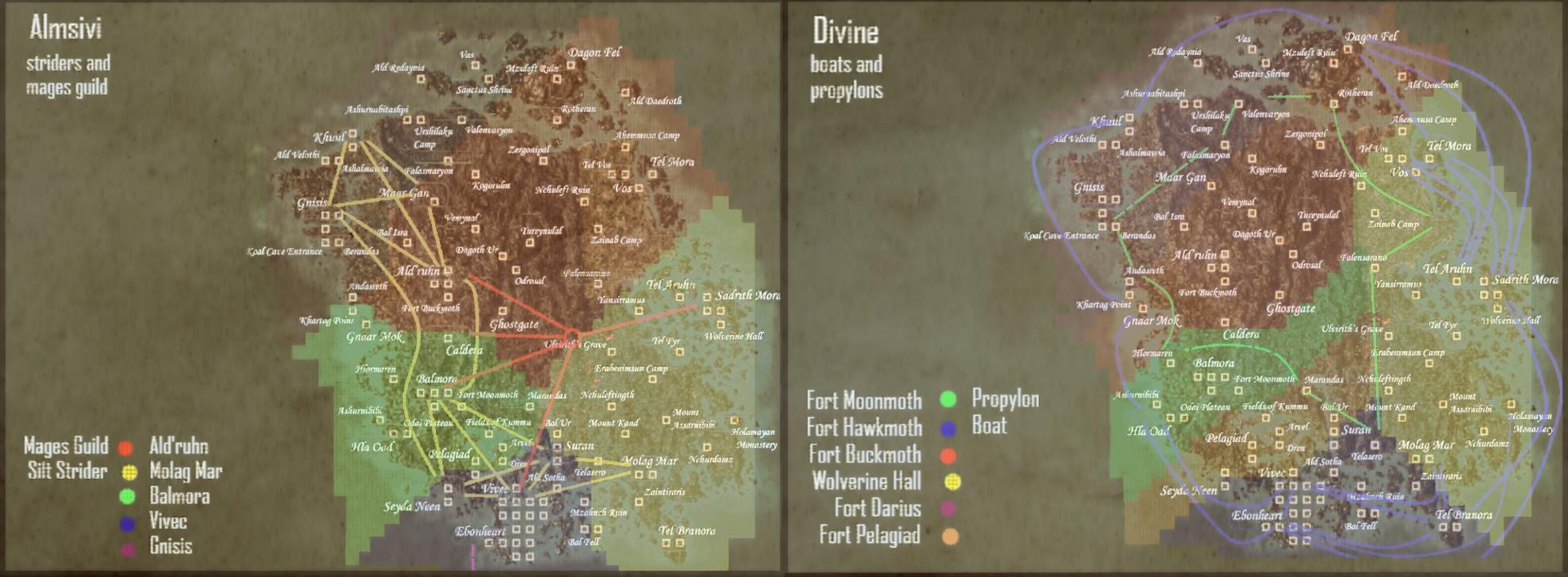

Spoiler alert: here’s Morrowind’s beautifully messy travel map, visualized. The chaos makes sense given the island’s geography and history. Credit goes to a Reddit user _Dialtone.

Spoiler alert: here’s Morrowind’s beautifully messy travel map, visualized. The chaos makes sense given the island’s geography and history. Credit goes to a Reddit user _Dialtone.

Hell, even cantons within the capital city of Vivec have gondoliers. There’s ton of fast travel options across Morrowind, and learning them pays off. Players who pay attention, who learn about the lore and geography get rewarded. In a game with a lot of walking, zipping around the island - and doing so because of your own skills - feels incredible.

This rewards players who take the time to learn and understand the geography and even geopolitics of Vvardenfell. There’s a whole new layer of a game here, and I love that you never have to “step out” of a game to fast travel.

Let’s contrast that with Morrowind’s successors: Oblivion and Skyrim - both of which I love for different reasons, which is a disclaimer I feel the need to make, because of what I’m going to say. Fast travel in these games sucks and makes the world so much smaller, and makes the player feel so much less connected to the world.

Oblivion’s map is twice the size of Morrowind’s. Yet, it feels like the world is only a fraction of the size - and in big part that’s because of the ease of navigation and prevalence of fast travel. You can fast travel at any point (as long as you’re outside and not in combat), and you can instantly appear in any area you already visited. Worse, the game starts with fast travel to all of the game’s major cities unlocked. So you don’t even have to discover the cities even once. You may never see the major roads in Oblivion, because you don’t really have to.

The roads, and overall flatter geography in the game contributes to the feeling of the smaller world. Morrowind is mountainous, and misses a developed road network. Yes, there are roads, but the cities aren’t particularly well connected, and you have to figure out where the road exist. Roads don’t show up on an in-game map, so you might want to ask a guide or pick up a book (yup, a book) which describes how to make your way across Vvardenfell.

The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion (remake): So many beautiful vistas, it’s too bad there’s no practical reason to truly take them in.

The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion (remake): So many beautiful vistas, it’s too bad there’s no practical reason to truly take them in.

Skyrim is not much better in this regard. There’s a diegetic (read: in-game) ox cart system which lets you fast travel across the major cities, although the only reason you’d use that is to discover the city for the first time (that is, skipping the trip again). Outside of that, you can fast travel to any location you’ve already visited.

This makes the world feel so much smaller - distance is never a consideration when you can fast travel to the city, dump your loot, restock on supplies, and return back to your adventure in an instant.

Some games offer a slightly better in-game fast travel option.

Witcher 3: Wild Hunt lets the player travel between discovered signposts. While those can be a little too common, in combination with a built-in quest GPS they dissuade players from learning the lay of the land. We remember Witcher 3 for its characters and stories, but the world is not as well connected in player’s head because of the abundance of signposts.

And it’s a shame, because the world is gorgeous. CD Projekt Red built one of the most visually stunning open worlds of its generation - and I spent most of it staring at the minimap, following a little dotted line. NPCs give you directions during quests. Detailed directions! And I couldn’t tell you a single one, because why would I listen when there’s a quest marker?

The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt - This is an isolated archipelago of Skellige. Then why can I easily hop there and back with a click of a button?

The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt - This is an isolated archipelago of Skellige. Then why can I easily hop there and back with a click of a button?

The signposts also flatten the world’s geography in a weird way. Skellige is supposed to be a remote, dangerous archipelago - with a voyage across treacherous seas to get there. You do that voyage exactly once, in a story mission. After that? You can teleport from a Novigrad back alley to Skellige’s frozen shores and back at an instant. The sense of remoteness, the idea that Skellige is far, evaporates. Everything is one click away from everything else, and the world shrinks.

Ubiquitous, singular fast travel networks like this tend to do that - they don’t encourage or reward learning the specifics of how the world operates. Just find a signpost, open the map, click where you want to go.

Dragon’s Dogma: Dark Arisen has portcrystals - teleportation stones in its major hubs. But it also lets you place a limited number of portcrystals anywhere you want, creating your own teleportation network. This encourages the player to think about the world critically - what areas will they likely need to come back to and which points of interest can serve as a convenient transportation hub. As the player learns more about the world, they can move their portcrystals as well - so you’re not locked into the choices you made. It’s really satisfying when you get to shorten a long trek to a quest objective because of your own foresight.

I didn’t have a fitting screenshot for Dragon’s Dogma: Dark Arisen here, so enjoy the game’s amazing monster battles.

I didn’t have a fitting screenshot for Dragon’s Dogma: Dark Arisen here, so enjoy the game’s amazing monster battles.

Dragon’s Dogma 2 also introduced a second transportation system - ox carts. Ox carts are also cool because they might get ambushed - introducing additional considerations to fast travel. Ambushes can be no joke too, so you really have to consider how you want to traverse the world.

Moving to massively multiplayer examples, vanilla World of Warcraft (or World of Warcraft Classic) touch on the idea of interconnected travel systems. Walking places in vanilla World of Warcraft is always long, and the game has a system of connected flight paths - for a fee, a flight master would let you take a flying beast to any of its connected locations. But those aren’t instant, the flight happens in real time, and the longer flights can take up to 10-15 minutes. But flight paths connect to other transportation networks.

Alliance cities of Stormwind and Ironforge are connected by an underground tram system, which is significantly faster than taking a flight. It’s also free - Alliance tax dollars at work! Other cities and towns might be connected by ships or zeppelins. All of which take a different amount of travel time - and an experienced player would know to take a ship followed by a flight path followed by a tram ride and arrive 20 minutes earlier than the player who simply took a flight path. The systems encourage mastery, which immerses players deeper into the game.

And then there’s the Old School RuneScape. Oh boy. The game’s default walking speed is atrociously slow and the running energy is limited. Quests have a tendency to send you all over the world, and learning to navigate the world pays off. This being RuneScape - one of the grindiest games out there - most fast travel methods need to be unlocked by either improving skills or completing quest chains. But as you play, you open up more and more ways of traversing the world of Gielinor. You start off with a free spell which teleports you to Lumbridge - the game’s starting location. Nice. As you train up magic, more and more teleports to other major cities open up, although each one costs resources - runes.

Old School RuneScape is filled with atomic transportation networks. Here’s a fairy ring, although my character hasn’t completed the required quests to unlock them yet.

Old School RuneScape is filled with atomic transportation networks. Here’s a fairy ring, although my character hasn’t completed the required quests to unlock them yet.

Then of course you have your ship networks. Not every ship visits every location, so you need to know which routes are offered by each ship captain. Then there are the spirit trees, which only grow in certain locations. Gnome gliders, magic carpets, hot air balloons. Fairy rings with three-letter codes for each location. Wilderness obelisks. Teleportation amulets. Skill capes, which teleport the player to a relevant guild hall. And that only scratches the surface - the game is filled with atomic transportation systems, which are sparsely connected with one another. Access to these is often treated as a reward in its own right, with many players prioritizing quests unlocking new transportation options. A knowledgeable player can zip around the Gielinor in a matter of seconds.

So why did modern games turn away from this? Well, Skyrim sold over 60 million copies. Morrowind sold somewhere around 4 million. I’m not going to pretend there’s no lesson there.

Complex, interlocking travel systems require more from players. They require you to pay attention, to learn, to occasionally get frustrated and lost while being chased by the cliff racers. And modern players - myself included - don’t always have the patience or time for that. We have jobs. Kids. Other games in the backlog. Sometimes you just want to click on a map marker and be there.

I’ll be honest: when I need a comfort title, I boot up Skyrim, not Morrowind. Because Skyrim lets me turn my brain off. I can clear a dungeon, fast travel to Whiterun, sell my junk, and fast travel back - all in the span of a few loading screens. It’s frictionless. It’s easy. And easy sells.

There’s always another dungeon to clear in The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, always a clear next thing to do, always an arrow pointing you somewhere. I’m familiar with the world design of Skyrim, but that’s a artifact of playing the game so many times and for so long, not a result of in-game systems which require me to pay attention.

There’s always another dungeon to clear in The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, always a clear next thing to do, always an arrow pointing you somewhere. I’m familiar with the world design of Skyrim, but that’s a artifact of playing the game so many times and for so long, not a result of in-game systems which require me to pay attention.

Game designers know this: friction is risky. Friction makes players bounce off your game. Friction gets you a 6/10 review that mentions “dated design” and “rough around the edges”. So the industry optimized friction away, and in doing so, optimized away an entire dimension of gameplay.

Here’s what we’re losing: diegetic fast travel turns navigation into a skill tree. There’s no UI element tracking your mastery of Morrowind’s transit networks, no achievement pops when you figure out that Almsivi intervention from a certain location drops you right next to a Mages Guild teleporter. You worked hard for this knowledge. And that kind of mastery hits different than watching a progress bar fill up.

When you internalize a game’s geography - the world becomes real in a way map marker navigation can never replicate. You’re not following a GPS, you’re navigating. There’s a reason we don’t feel a sense of accomplishment when Google Maps gets us to a new restaurant. And be honest, you get a tinge of pride when you know your way around and turn off your GPS.

Which brings me back to Dragon’s Dogma 2, a relatively recent game following near extinct philosophy.

Dragon’s Dogma 2: Bigger, better, and even more intentional than its predecessor.

Dragon’s Dogma 2: Bigger, better, and even more intentional than its predecessor.

Capcom’s 2024 sequel has stubborn travel systems. In an era of waypoint-cluttered open worlds, Dragon’s Dogma 2 asks you to actually learn its geography. Portcrystals return - those placeable teleportation stones that force you to think critically about which locations deserve a fast travel point. And the ox cart system is back too, now with the very real possibility of getting ambushed by goblins mid-journey. Fast travel isn’t a menu. It’s a decision, with actual stakes.

The whole system was severely undercut by a microtransaction scandal: you could, and still can purchase portcrystals for real money. Yup, even if we ignore the ethics of microtransactions here, the scarce resource that makes you engage with a game on a deeper level can be made abundant with some cash. Which just undermines the entire system.

And yeah, I found the microtransactions here gross and distasteful.

But Dragon’s Dogma 2 did prove something - diegetic fast travel isn’t a relic of early 2000s. You can ship a game in this decade that asks players to learn its world, plan their routes, and treat navigation as a core part of gameplay rather than an inconvenience to be skipped.

Not every game needs seven interlocking transit networks, but the best open worlds are the ones where distance means something. Where getting from point A to point B is itself an engaging problem to solve. Where fast travel is a reward for mastering the game’s systems. Speaking of, I have a propylon index to track down in Morrowind.

Comments

Respond directly on Bluesky (threads shown below) or Medium (view comments there).

Rooslawn's Unmapped Worlds

Rooslawn's Unmapped Worlds