Death Stranding and the exploration of grief

My newborn son died almost 4 years ago. Yeah, that’s a heavy topic for a gaming blog, but I’ve been sitting on wanting to write down my thoughts on how my gaming hobby is a part of the healing process. Definitely a trigger warning - I won’t be talking about how things happened (those details are for my family and I), but I will talk in depth about how it made me feel. It’s not pretty.

“For sale: baby shoes, never worn.”

I woke up this morning from a haunting nightmare, thinking about my son.

4 years ago my world was shattered. Words can’t really describe the level of despair, pain, and grief that I felt. It’s unnatural, it’s sick, and humans aren’t really made to outlive their offspring. It’s probably single-handedly the worst thing that could happen to a person, and I’d trade the spots with my son in a blink of an eye if I had the option.

Death Stranding: loss, isolation, and the strands that bind us.

Death Stranding: loss, isolation, and the strands that bind us.

The pain never really goes away, either - the feelings ebb and flow, but it’s probably safe to say that at times it hurts the same today as it did 4 years ago. All grief therapy focuses on is building up your tolerance for feeling the pain, so that more of the pain and hurt can stay in you without overflowing and impacting the executive functioning.

I tried many things to help dull the pain. I went through a phase of overly generous donations to the causes dear to me. I was in therapy, naturally, where I had to do the work of growing my capacity for pain.

I tried connecting with people. Connecting with people was hard. Everyone was eager to offer their condolences, but no one really understood what I was going through. How could they? “My condolences, I understand what you’re going through, I had to put my dog down.” Oh fuck you, and no you don’t.

It’s a natural response, people would try to relate through their own lived experience - but that’s the thing, there isn’t anything like it. It’s not “like losing a loved one up but turned up to 11”, it’s a whole different kind of messed up. It’s even more insulting because it’s so messed up, alien, and unnatural that I myself don’t really understand what I’m going through. There are experiences you just can’t empathize with.

Death Stranding is set in a lonely and often gloomy world, with lots of time to think in between.

Death Stranding is set in a lonely and often gloomy world, with lots of time to think in between.

My therapist told me I’d have an easier time if I was a devout follower of faith, but I wasn’t, and quite frankly the sentiment from (some) of the more religious friends was even more insulting. “That’s okay, it’s all part of God’s plan”. Yeah, either your god is a giant dick, or you’re a vile person who can’t see other people through any other lens than the one that makes you feel most holy. I’m pretty sure it’s the latter. We’re not friends anymore.

Even further, you can’t even empathize as well with other parents who lost their kids. Because their hurt is whole kind of different than mine. When a child dies, all of your hopes and dreams die with them. Your relationship with parenthood, the reasons for having kids, a whole chunk of your relationship with your partner - all the individual pieces that make up bringing a kid into this world rot and decay. And all of those pieces are unique to you as a human.

Even my wife and I, despite going through every step of the journey hand-in-hand, had widely different experiences, and couldn’t truly understand what it’s like to be each other.

What I’m trying to say is that the relationship with grief, especially relationship with a loss of a child is a truly individual and unique flavor of fucked up, and there’s really no one size fits all for finding connection or meaning in things.

You can see hand prints from when the veil between worlds is thin. Sometimes the hand prints are small..

You can see hand prints from when the veil between worlds is thin. Sometimes the hand prints are small..

So, why is this on my (so far anonymous) gaming blog and not, say, a personal one? (I do have one)

It’s because this journey leads me to Death Stranding.

If you haven’t played, Death Stranding is set in a fractured America where a cataclysm has blurred the line between life and death, leaving the world haunted by invisible, ghostly apparitions of people long gone. The world of Death Stranding is filled with danger, it’s unnatural and isolated.

I played Death Stranding a year before my son died. If you’ve read my blog, you could probably tell that I deeply appreciated how the game makes you engage in navigation and mapping exercises, how strategic gameplay of planning out your route intersects with the minute-to-minute navigation of obstacles. I found the multiplayer functionality a perfect fit for the lonely, yet connected world. I enjoyed seeing Kojima’s passion about so many topics clearly shine through in every part of the game. Look, Kojima made you sit through a 2 hour ending cinematic and I’m pretty sure you did - and if that’s not passion for delivering a vision - I don’t know what is.

It’s a great game, which is underscored by how divisive it is - you either love it or hate it. I loved it, but I could clearly see why so many people didn’t. And I think that makes Death Stranding a great piece of art, and a damn good video game.

After my son died, I picked Death Stranding back up. I don’t recall why, but maybe I needed a distraction, or maybe in the back of my brain I remembered that the game tackles the subject of connection and loss.

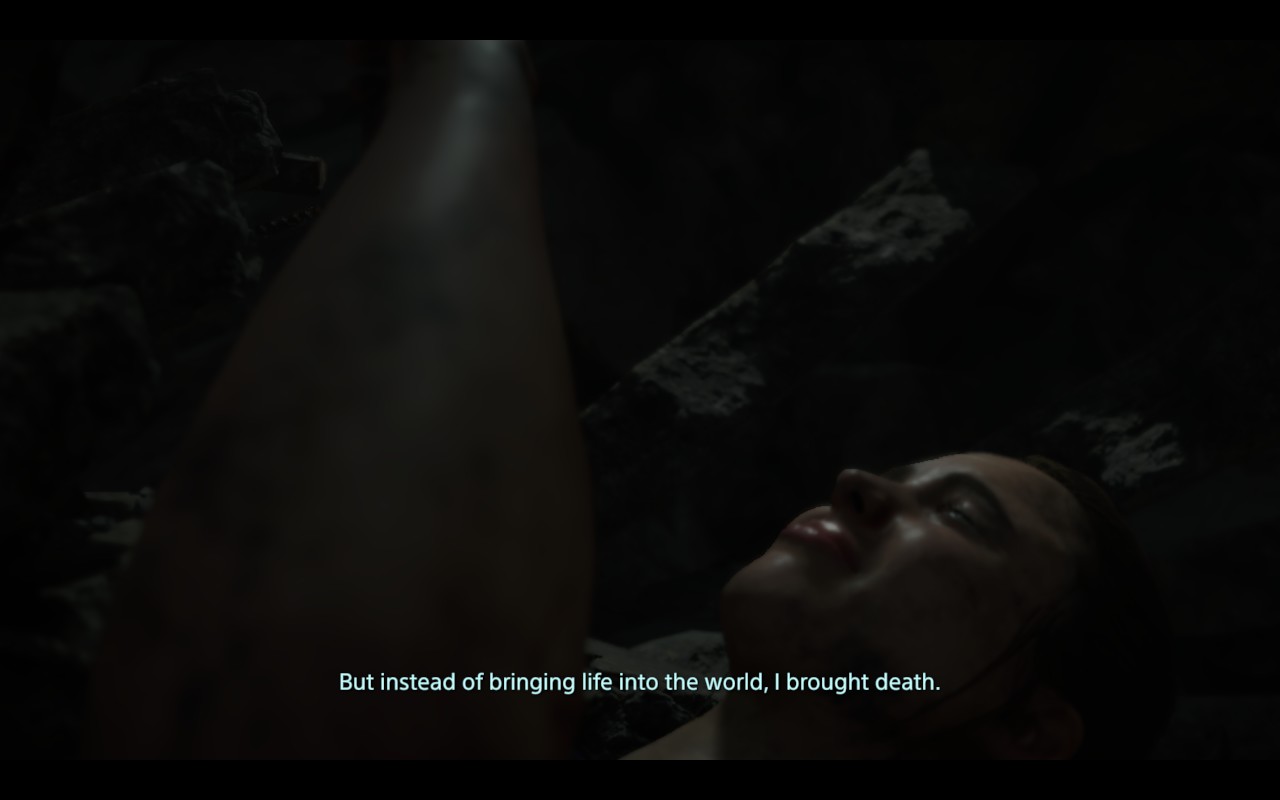

This hit hard. I’ve heard my wife say that before, and it rips my soul apart every time.

This hit hard. I’ve heard my wife say that before, and it rips my soul apart every time.

And it connected with me on a whole another level - much deeper, tugging at the heart strings in a unique way that worked for me. Needless to say, I cried a lot when playing. It was therapeutic.

Sam, the game’s protagonist, is an emotionally withdrawn man with aphenphosmphobia - a pathological fear of physical and emotional intimacy. Sam never asked for the journey, but the choice wasn’t presented.

Sam’s long voyages turned into an opportunity to reflect and slowly process, while I’m focusing on taking one digital step at a time.

Lou - the baby in a pod - a bridge between the world of the dead and the living is the only way for Sam to see and avoid the ghostly apparitions inhabiting the desolate landscape. Lou - not quite dead nor alive, was a transitional surrogate baby I could channel my mixed emotions into. BB would giggle when Sam ran really fast and would cry when the danger was near. I’d always take the time to soothe Lou, I wanted to be a good dad.

I vividly remember my wife flinching when she’d hear Lou cry. No two journeys are the same. Yeah, this was therapeutic for me but my partner doesn’t have the same relationship with video games I do, and hearing this digital baby cry caused more hurt to a woman who’s been through hell. It sucked, and I tried to play Death Stranding with headphones on, and sometimes on a smaller screen. There’s probably something profound that can be said about isolation and connection here.

Nature is cruel, and the body doesn’t know there’s no child to feed.

Nature is cruel, and the body doesn’t know there’s no child to feed.

The game’s cast of characters were no longer quirky plot devices.

Mama is a scientist who is physically and spiritually tethered to the ghost of her infant daughter. Because of this connection, Mama cannot leave the ruins of her lab, living in a state of arrested grief, trapped by her loss. Now, Mama turned from an unnerving side character to a someone I could - if not understand - tragically relate to. While not the same, Mama gave birth to a stillborn. I would wail every time Mama would go on screen.

Cliff Unger, one of the game’s supernatural antagonists, is slowly revealed to be Lou’s father (sorry - spoiler I guess). His ghostly rage and sorrow, his ability to come back from the dead is fueled by his unyielding, fierce love for his child. I can feel Cliff’s indescribable pain and anger of having a child stolen from you by fate. He’s an embodiment of a broken parental promise and all I can hear is “I couldn’t protect my child” thumping in my head over and over again.

Cliff Unger: a manifestation of rage of a father that never was.

Cliff Unger: a manifestation of rage of a father that never was.

Heartman is a researcher who deliberately stops his own heart every 21 minutes to spend a few moments in the afterlife, relentlessly searching for the lost spirits of his wife and daughter. Heartman’s obsessive search to join his family on the other side tugged on a relatable desire to regain control, to do something about the situation. I wish I could.

Even Fragile, a woman whose own body is ravaged by timefall - a supernatural rain that rapidly ages everything a touches, is a symbol of perseverance and human’s ability to tolerate pain and move forward, even if it’s sometimes not entirely clear why.

Playing Death Stranding hurt, as I processed my emotions in relation to the game’s cast. It hurt to be so close to the themes the game explores. But it hurt less than dealing with those emotions directly. Death Stranding became a safe space, where for once the pain wasn’t mine, and I could feel it in bite sized chunks, and I could think about death and loss without losing a grasp on reality.

This was a place for me to practice feeling feelings, to build up capacity for pain, to disassociate from self, so I could in time deal with my own loss. It sucked, but it sucked in a way that helped me get better at dealing with pain. Death Stranding was helpful to my journey. It didn’t heal me, but it gave me space to do the work that I needed to take my journey through grief one step at a time.

Comments

Respond directly on Bluesky (threads shown below) or Medium (view comments there).

Rooslawn's Unmapped Worlds

Rooslawn's Unmapped Worlds